From WhiteFungus.com

From WhiteFungus.com

“When I was born there were dead bodies hanging off nooses in the streets of downtown Baghdad.”

“I feel it necessary to say here…that the two basic sentiments of my childhood which stayed with me well into adolescence, are those of a profound eroticism, at first sublimated in a great religious faith, and a permanent consciousness of death.” – Luis Buñuel

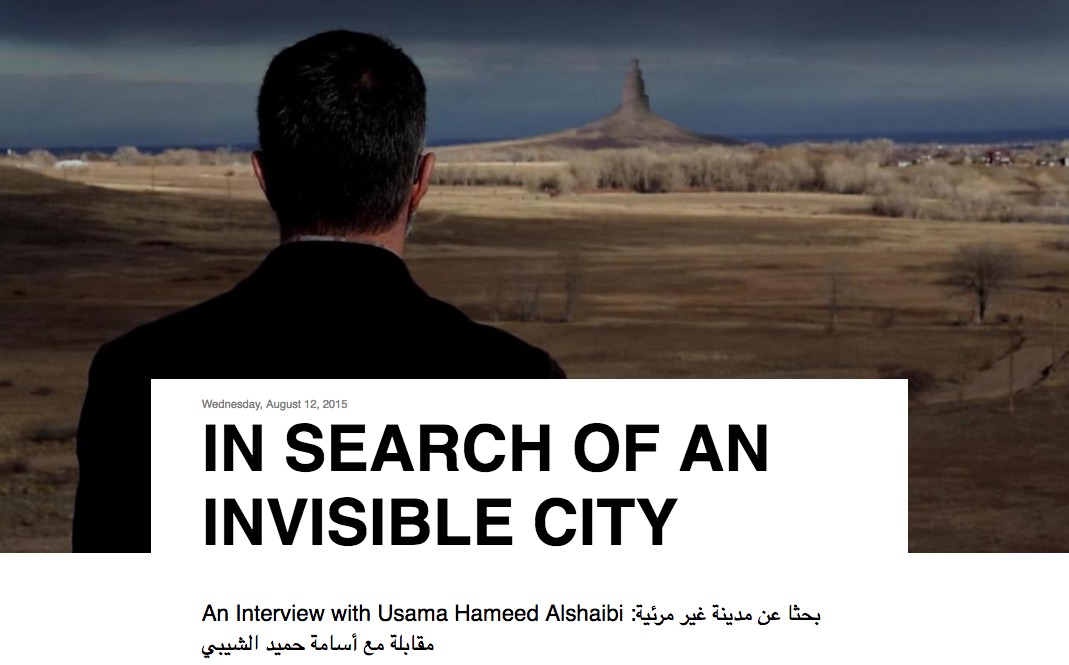

So begins the “Forced Artist Statement” of underground filmmaker Usama Alshaibi, whose brilliant new work Baghdad, Iowa depicts a dreamlike search for a liminal, mythical homeland amidst an autobiographical tangle of grief and lust and the director’s divergent roots in the Midwest and the Mideast. Usama has made around 75 films to date, ranging from wild erotic shorts to experimental narratives to the documentaries for which he is perhaps most widely renowned. His work tends to be predicated on the concept of the “other”, the immigrant, the outsider, and how this position relates to fetishization or violence- often utilizing his lived experience as an Arab American; and a singular style bursting with lysergic irreverence as well as a deeply genuine, intimate, vérité.

Alshaibi appears onscreen in many of his films. He also appears in two very different books: In 2003, Baghdad born Usama Alshaibi is interviewed in Pulitzer Prize winning author Studs Terkel’s Hope Dies Last, a strident oral history of contemporary American perseverance. Here he speaks lucidly about his childhood between Iraq and Iowa, his loving relationship with his all-American wife Kristie, the struggles facing Arab-Americans after 9/11, and his own path to becoming a US citizen. Conversely, Deathtripping: The Extreme Underground, Jack Sargeant’s landmark paean to the Cinema of Transgression, paints a very different portrait as it details the content of Usama’s short films (often produced with his wife Kristie), “characterized by a combination of dark humor and a gleeful celebration of what is deemed by mainstream culture to be ‘deviant’ behavior, this includes rectal masturbation, bloody violence, male prostitution and fake porno film auditions.”

The stark contrast of these two mentions depicts an irreducible artist. Usama is fascinated with the paradox that occupies the conceptual space between dualities: Iraqi and American, activist and libertine, repulsion and attraction, Eros and Thanatos- dualities which find vibrant concert in his work. By his own estimation, the 2011 experimental narrative Profane is the most complete in this regard: in the film documentary and narrative footage interweave, as do twin itineraries of sexual transgression and religious transcendence.

His widely acclaimed 2006 documentary Nice Bombs details Usama’s 2004 return to Baghdad during of the US invasion with his father and wife. The Alshaibi’s literal home videos in Iraq depict a people not at some ideological remove, but in their living rooms; having dinner, conversations, dances, and voicing everyday concerns; intermittently, impersonally (and sometimes finally) interrupted by “nice bombs”. Even in the context of such political extremes and abstract violence, Alshaibi illuminates how through the concept of home an authentic shared subjectivity emerges that withstands the deterritorializing force of the war machine, even if the structural home may not:

His other homeland, its epicenter somewhere around Iowa City, became the focal point of an amorphous multimedia project that would intermittently obsess Usama after his return to the United States. Amid the grief following his younger brother’s untimely passing from a drug overdose, he began to explore their childhood home in America. Glimpses could be found online of the project, christened Baghdad, Iowa, as it began to coalesce into a film.

“The origin, or the seed, of this invisible city was planted shortly after my brother died at the age of 28. He was a writer, a religious man, a husband, a criminal and drug addict. When they were preparing my brother’s tombstone they asked my mother where he was born, and she said he was born in Iraq. Even though he was born in Iowa. Where are we? Perhaps his death birthed this place.

It’s that spell that has lit up the cornfields.”

The nascent film was violently sidelined when Alshaibi was assaulted during a visit to his home state, the impetus for the attack being his ethnic name. The hate crime would serve as a catalyst for his acclaimed tour de force documentary American Arab, autobiographical examination of family, racism, and Arab/Muslim identity in post 9/11 United States:

Usama since resumed his search for Baghdad, Iowa, and his years of work have culminated in a otherworldly poetic narrative, 34 of the most haunting and beautiful minutes he has yet produced. Here, in a conversation from last year during production, the director delivers a report on the expedition, and shares generous insight into his life and work.

N: In your earlier work it was clear you were making do with whatever you could get your hands on. Now it seems like you have a crew and some equipment. Could you talk about your trajectory as it relates to being able to produce films, and where you started?

U: I began making work at a certain time in the mid 90’s. I came up at a time when the Dogme 95 movement was popular, and that was an interesting philosophy. I also come from a tradition of underground filmmaking. I always get annoyed when I meet other filmmakers who just took so long to get one film, or even one shot off the ground because they needed money, crew, or cast. It’s like “look, we have the equipment. What’s the problem?”

N: A lot of filmmakers have their work described as “personal”, it’s a bit of a cliche. But in your case the term is critically apt, as your work is extremely open to your personal experience. Do you feel like creating a familial environment enables or assists that?

U: In Chicago, at film school there, I made a lot of friends and ended up working with the same people over and over. Of course as my films evolved, I would gravitate towards people who were aesthetically close to me. So it depends. I would watch their films and would think, ah, we kind of have a similar sensibility. It’s absolutely about building and working with the same people over and over, and having a relationship. Some directors that I knew had very distant relationships with their actors and performers, saw them as objects. That’s fine, that is one artistic approach, but personally I approached it from a more emotional point of view. I really want the actors and performers to trust me, because I want to take them to some interesting places. I need them to be flexible as performers to go there. I have relationships with them. I don’t really “hang out with my friends”, I work with people- and that’s my “hang out”. They’re my friends, and they’re work buddies, colleagues. That, for me, is a good way of working with people.

N: The first film that I saw of yours was Nice Bombs, and then of course American Arab. Both of these are very much in the mode of the man with the camera, with a crew or without. Both are about you and your family, so I suppose that informs my idea of a personal, familial approach to filmmaking.

U: You are also talking about the culture I came from.

N: Could you tell me a little bit about your upbringing and where you were born and grew up?

U: I was born in Baghdad, Iraq in the fall of 1969, it was a very tumultuous year. In that period, Iraq had been going through a few revolutions. It had similar problems then as it does today. My mom was originally from Palestine, her family had left because of the problems that were erupting over there. This was in ‘48, of course many Palestinians fled during the formation of Israel. Baghdad was a viable option, and there she met my dad and they had me, I was their first. I had two sisters after that.

Then my father got a scholarship to study in Iowa City, Iowa. I went to grade school there, I became Americanized as they say. English was the first language I learned to write even though I was speaking Arabic. When I came back to Iraq, I was seen as an American kid- which was interesting. When I returned, Saddam Hussein was gaining power, and my father- who comes from the Shia side of Islam was, shall we say, encouraged to join the Baath party, and he refused. In this case, you are basically blacklisted, and are seen as a kind of traitor. That led us to the south of Iraq. During that time was when the Iraq & Iran war started, which was the beginning of our family’s exile from that country and finding our way in the world. I grew up in a kind of cross culture, where I was surrounded by influences from growing up in the culture of Middle East and as well as the United States in that time. I stopped really identifying with either of them, and was just more into what I was into. The painting and the interest in art led me to various subcultures. I was really interested in things that went on in the American 60’s, discovered punk, discovered drugs, discovered LSD. I think that was a definitely a defining moment as a young person, being made aware that reality and the world have other faces that are unseen, other spaces you can go to. It opened my eyes to who I was. These influences were the things that were affecting me, along with the politics of who I was. You have to understand also that I didn’t have a stable immigration status, so when I came to the country I lived under my mom’s visa, but when that ran out I would have no status, and have to be deported. When the first Gulf War started back in 91, when we first attacked Iraq- Gulf War One, you remember that one.

N: My whole class was given a celebratory T-shirts with a fighter jet on it at a school assembly, a bizarre scene.

U: And the yellow ribbons for the troops. Well, as I had “no status”, I was being deported. I had to go before an immigration judge and fight for my case, to say “if I went back to Iraq, it would have a death sentence”. I would have to go to Saddam’s army, and I would be fighting American soldiers, ridiculous. I wasn’t going to do it.

N: How old were you when you had to make this case?

U: I was 22. At that time, if you were a child protected under your mom’s visa, that would expire at 21. Of course if I was being deported, I would have to serve in the Iraqi army. So my immigration status for the majority of my adult life was “political asylee”. That also kept me from doing certain things, because before I got my citizenship I wasn’t able to work legally. I would travel, but I couldn’t take certain jobs. I would wash dishes, I would do janitorial stuff, I would do work that no one cared about. I just wanted them to leave me alone because I didn’t have anything to prove I was an American citizen, and I didn’t have any proof I could work legally. So that’s how I got by and I was able to get a better status. That’s how I navigated through the United States.

As I got older, into my 20’s, I thought I would like to go back to school and do something with myself. I felt like I was so lost for most of that time. By my mid 20’s, I did go to film school and that’s where I found my voice. I think I found something in that that I didn’t have when I was drawing and painting.

N: Listening to your story I was thinking about what that constant state of “otherness” must have been like for you, in both Iraq and Iowa.

U: I do think that where you’re from and what is going on politically with the United States has an impact on how you see yourself and how you grow up. Japanese Americans during World War 2 had a very different experience as opposed to being Japanese American right now. It’s loosely comparable historically to what happened in the 70’s with Arab Americans, because of tensions with Iran, but the American concept of “Arab” was still the oriental carpet, the genies and riches. Back then things were kind of mild.

Later on, with the Gulf War and the way it vilified Saddam Hussein, and then of course post 9/11, I can tell, it’s in the air.

Not having the legal definition of “who you are” also kind of effects you. I was kind of in this nowhere zone for awhile. When I was living in Iowa City I used to work at this restaurant as a dishwasher and my boss was actually from Algeria. He had this thick accent, his English wasn’t great but he was losing his Arabic- He was in this limbo. He didn’t quite completely have the English language down, but he had completely lost the Arabic language. In a way you do choose it, or it chooses you- like one pulls you further. I really truly do think I’m an American, but that’s not in opposition to anything else. Of course it would be difficult for me to go back to certain countries in the Middle East and fit in, but I’m okay with not fitting in. And really, there are other people like me. I definitely feel like a contemporary citizen in that I have this duality, and I think it will be more common. People can grow up in multiple cultures. It’s no longer “I was born in this town and grew up in this town and I’m going to die in this town”.

N: It’s not really possible so much anymore is it? We have the entire world at our fingertips.

U: Also, often people who come from countries that are in conflict are spread all over the world, because you can’t go back.

N: I do want to talk about Baghdad, Iowa as a film and as a concept. You talk about being of two places. People often search for a home, in many different ways. In many ways you identify as an American, but also it seems as you lived through these various states of flux you found a home within an imaginary space, that within your imagination there was a constant place for you.

U: Absolutely, yeah.

N: Bagdad, Iowa, as you have said, is an imaginary place that you are “circling closer and closer to”, as if you are being pulled. I think this concept of places having a psychic gravity is quite interesting. What is the pull of Iowa for you, on a real or symbolic level?

U: I think the gravity of the place is very much connected to the earth, and growing up there. There is something very truthful and important there, our experience there as a family and who I was, and my friendships. Everything I experienced there connected me to the land. I hear some of my relatives in Palestine talk about missing their homeland, or Iraqis who cannot go back to Baghdad and the love they have of their land, but wherever they are, they can bring it. They make the same food, they have the same friends around them, they are listening to their favorite music. That is a kind of a conceptual experience you can take almost anywhere. So, I was kind of still growing up in the Middle East in a way, even though I was in Iowa. We would go to mosque and surround ourselves with other Arab families. There is this common experience even though we are not necessarily in our native land. It’s a new experience and a unique fit, and it’s not necessarily based on the strategies of a lot of the European settlers. It’s a new idea of what this land could be. I didn’t realize that until much later.

Also, I grew up not completely having a solid home, so things like my movies and books, my family, wherever we took that, it was home. So really I’m expanding that into something that can be a place itself. That can exist because, in a way, I willed it to. It’s funny how you put it, the gravity of it pulls these scenes and visuals and words from me that I’m reflecting back to it. And it absolutely becomes this very specific thing. Even when I talk to people about it, it’s almost like it is a real thing. You can do a Google search for Baghdad, Iowa and it has become a real place. At one point, I remember my daughter was asked “where is your dad from?” and she said “Baghdad, Iowa”. I make films, studied art a little bit, I love the idea of art making as process- but I love the idea of it being connected to something real, even if it is conceptual. So absolutely it speaks from a real place. It’s all these experiences connected. It is something unified. Maybe earlier on it was a bit more abstract but now becoming more literal. I have clothing from the natives of Baghdad, Iowa that has been made I have started to collect recipes of Baghdad, Iowa. I have profiles of these subjects. Even though the film is going to be very fleeting, I’m developing real people. That’s definitely pulling me into the gravity of the film. I am getting closer to it.

N: I wanted to ask you about the young man who assaulted you in Iowa. How do you consider that event in relation to Baghdad, Iowa?

U: I think that I’ve taken aspects of the violence that happened to me and made it almost collective. I’ve taken a lot of things that I have seen around me, incorporated things that can happen in Iowa, young men that have a lot of rage and find someone vulnerable. It can also be young men with guns at checkpoints in Iraq. What actually happened to me has informed it, there is that position in there of that violence, of that assault. And I think that violence is always going to recur in some way. What happened to me is a big part of the film, and in a way it is almost repeated. I reenact it, fictionalize it.

I think a lot of this project, Baghdad, Iowa, is a way for me to try and figure out all of this that has been going on in me. An internal psychic process that’s being reflected, being projected, with film, with images and words. Perhaps trying to make some sense of that chaos. In a way making it more poetic, maybe trying to grasp something with it. I’m not entirely aware of how it is being processed, but I’m aware that I’m using how I felt being traumatized, being afraid.

There are also elements of what turns me on, what’s mysterious to me, that are driving the film as well. I had been thinking about it, through all of my experiences growing up in Iowa, and they were really profound. The assault on me was another profound experience in it’s own way, and I guess at this particular time I’m not interested in making a moral statement about it. I just want to keep this experience, and maybe in a way when I objectify what happened to me to look outside of it, it’s more interesting than being inside of it and being a victim of it. It’s the way I work. I’m able to pull out and I’m no longer who I am so much as part of this larger construction, the movement, the emotions and people having to deal with each other in this state. So I begin to better see myself that way.

—

Usama Alshaibi currently makes his home in Boulder, Colorado with his daughter Muneera. Baghdad, Iowa was completed on June 29th, 2015. Upcoming screenings include the Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur, the short film festival of Switzerland, with more to be announced soon.

Excerpts from Usama’s notebook for Baghdad, Iowa (featuring drawings, collage, and a short story) will be featured in MIDWASTE, a forthcoming publication.