Host Janaan Hashim interviews me on Radio Islam on my broadcast premiere of American Arab and the identity of Arabs in America today.

Host Janaan Hashim interviews me on Radio Islam on my broadcast premiere of American Arab and the identity of Arabs in America today.

From WhiteFungus.com

“I feel it necessary to say here…that the two basic sentiments of my childhood which stayed with me well into adolescence, are those of a profound eroticism, at first sublimated in a great religious faith, and a permanent consciousness of death.” – Luis Buñuel

So begins the “Forced Artist Statement” of underground filmmaker Usama Alshaibi, whose brilliant new work Baghdad, Iowa depicts a dreamlike search for a liminal, mythical homeland amidst an autobiographical tangle of grief and lust and the director’s divergent roots in the Midwest and the Mideast. Usama has made around 75 films to date, ranging from wild erotic shorts to experimental narratives to the documentaries for which he is perhaps most widely renowned. His work tends to be predicated on the concept of the “other”, the immigrant, the outsider, and how this position relates to fetishization or violence- often utilizing his lived experience as an Arab American; and a singular style bursting with lysergic irreverence as well as a deeply genuine, intimate, vérité.

Alshaibi appears onscreen in many of his films. He also appears in two very different books: In 2003, Baghdad born Usama Alshaibi is interviewed in Pulitzer Prize winning author Studs Terkel’s Hope Dies Last, a strident oral history of contemporary American perseverance. Here he speaks lucidly about his childhood between Iraq and Iowa, his loving relationship with his all-American wife Kristie, the struggles facing Arab-Americans after 9/11, and his own path to becoming a US citizen. Conversely, Deathtripping: The Extreme Underground, Jack Sargeant’s landmark paean to the Cinema of Transgression, paints a very different portrait as it details the content of Usama’s short films (often produced with his wife Kristie), “characterized by a combination of dark humor and a gleeful celebration of what is deemed by mainstream culture to be ‘deviant’ behavior, this includes rectal masturbation, bloody violence, male prostitution and fake porno film auditions.”

The stark contrast of these two mentions depicts an irreducible artist. Usama is fascinated with the paradox that occupies the conceptual space between dualities: Iraqi and American, activist and libertine, repulsion and attraction, Eros and Thanatos- dualities which find vibrant concert in his work. By his own estimation, the 2011 experimental narrative Profane is the most complete in this regard: in the film documentary and narrative footage interweave, as do twin itineraries of sexual transgression and religious transcendence.

His widely acclaimed 2006 documentary Nice Bombs details Usama’s 2004 return to Baghdad during of the US invasion with his father and wife. The Alshaibi’s literal home videos in Iraq depict a people not at some ideological remove, but in their living rooms; having dinner, conversations, dances, and voicing everyday concerns; intermittently, impersonally (and sometimes finally) interrupted by “nice bombs”. Even in the context of such political extremes and abstract violence, Alshaibi illuminates how through the concept of home an authentic shared subjectivity emerges that withstands the deterritorializing force of the war machine, even if the structural home may not:

His other homeland, its epicenter somewhere around Iowa City, became the focal point of an amorphous multimedia project that would intermittently obsess Usama after his return to the United States. Amid the grief following his younger brother’s untimely passing from a drug overdose, he began to explore their childhood home in America. Glimpses could be found online of the project, christened Baghdad, Iowa, as it began to coalesce into a film.

“The origin, or the seed, of this invisible city was planted shortly after my brother died at the age of 28. He was a writer, a religious man, a husband, a criminal and drug addict. When they were preparing my brother’s tombstone they asked my mother where he was born, and she said he was born in Iraq. Even though he was born in Iowa. Where are we? Perhaps his death birthed this place.

It’s that spell that has lit up the cornfields.”

The nascent film was violently sidelined when Alshaibi was assaulted during a visit to his home state, the impetus for the attack being his ethnic name. The hate crime would serve as a catalyst for his acclaimed tour de force documentary American Arab, autobiographical examination of family, racism, and Arab/Muslim identity in post 9/11 United States:

Usama since resumed his search for Baghdad, Iowa, and his years of work have culminated in a otherworldly poetic narrative, 34 of the most haunting and beautiful minutes he has yet produced. Here, in a conversation from last year during production, the director delivers a report on the expedition, and shares generous insight into his life and work.

N: In your earlier work it was clear you were making do with whatever you could get your hands on. Now it seems like you have a crew and some equipment. Could you talk about your trajectory as it relates to being able to produce films, and where you started?

U: I began making work at a certain time in the mid 90’s. I came up at a time when the Dogme 95 movement was popular, and that was an interesting philosophy. I also come from a tradition of underground filmmaking. I always get annoyed when I meet other filmmakers who just took so long to get one film, or even one shot off the ground because they needed money, crew, or cast. It’s like “look, we have the equipment. What’s the problem?”

N: A lot of filmmakers have their work described as “personal”, it’s a bit of a cliche. But in your case the term is critically apt, as your work is extremely open to your personal experience. Do you feel like creating a familial environment enables or assists that?

U: In Chicago, at film school there, I made a lot of friends and ended up working with the same people over and over. Of course as my films evolved, I would gravitate towards people who were aesthetically close to me. So it depends. I would watch their films and would think, ah, we kind of have a similar sensibility. It’s absolutely about building and working with the same people over and over, and having a relationship. Some directors that I knew had very distant relationships with their actors and performers, saw them as objects. That’s fine, that is one artistic approach, but personally I approached it from a more emotional point of view. I really want the actors and performers to trust me, because I want to take them to some interesting places. I need them to be flexible as performers to go there. I have relationships with them. I don’t really “hang out with my friends”, I work with people- and that’s my “hang out”. They’re my friends, and they’re work buddies, colleagues. That, for me, is a good way of working with people.

N: The first film that I saw of yours was Nice Bombs, and then of course American Arab. Both of these are very much in the mode of the man with the camera, with a crew or without. Both are about you and your family, so I suppose that informs my idea of a personal, familial approach to filmmaking.

U: You are also talking about the culture I came from.

N: Could you tell me a little bit about your upbringing and where you were born and grew up?

U: I was born in Baghdad, Iraq in the fall of 1969, it was a very tumultuous year. In that period, Iraq had been going through a few revolutions. It had similar problems then as it does today. My mom was originally from Palestine, her family had left because of the problems that were erupting over there. This was in ‘48, of course many Palestinians fled during the formation of Israel. Baghdad was a viable option, and there she met my dad and they had me, I was their first. I had two sisters after that.

Then my father got a scholarship to study in Iowa City, Iowa. I went to grade school there, I became Americanized as they say. English was the first language I learned to write even though I was speaking Arabic. When I came back to Iraq, I was seen as an American kid- which was interesting. When I returned, Saddam Hussein was gaining power, and my father- who comes from the Shia side of Islam was, shall we say, encouraged to join the Baath party, and he refused. In this case, you are basically blacklisted, and are seen as a kind of traitor. That led us to the south of Iraq. During that time was when the Iraq & Iran war started, which was the beginning of our family’s exile from that country and finding our way in the world. I grew up in a kind of cross culture, where I was surrounded by influences from growing up in the culture of Middle East and as well as the United States in that time. I stopped really identifying with either of them, and was just more into what I was into. The painting and the interest in art led me to various subcultures. I was really interested in things that went on in the American 60’s, discovered punk, discovered drugs, discovered LSD. I think that was a definitely a defining moment as a young person, being made aware that reality and the world have other faces that are unseen, other spaces you can go to. It opened my eyes to who I was. These influences were the things that were affecting me, along with the politics of who I was. You have to understand also that I didn’t have a stable immigration status, so when I came to the country I lived under my mom’s visa, but when that ran out I would have no status, and have to be deported. When the first Gulf War started back in 91, when we first attacked Iraq- Gulf War One, you remember that one.

N: My whole class was given a celebratory T-shirts with a fighter jet on it at a school assembly, a bizarre scene.

U: And the yellow ribbons for the troops. Well, as I had “no status”, I was being deported. I had to go before an immigration judge and fight for my case, to say “if I went back to Iraq, it would have a death sentence”. I would have to go to Saddam’s army, and I would be fighting American soldiers, ridiculous. I wasn’t going to do it.

N: How old were you when you had to make this case?

U: I was 22. At that time, if you were a child protected under your mom’s visa, that would expire at 21. Of course if I was being deported, I would have to serve in the Iraqi army. So my immigration status for the majority of my adult life was “political asylee”. That also kept me from doing certain things, because before I got my citizenship I wasn’t able to work legally. I would travel, but I couldn’t take certain jobs. I would wash dishes, I would do janitorial stuff, I would do work that no one cared about. I just wanted them to leave me alone because I didn’t have anything to prove I was an American citizen, and I didn’t have any proof I could work legally. So that’s how I got by and I was able to get a better status. That’s how I navigated through the United States.

As I got older, into my 20’s, I thought I would like to go back to school and do something with myself. I felt like I was so lost for most of that time. By my mid 20’s, I did go to film school and that’s where I found my voice. I think I found something in that that I didn’t have when I was drawing and painting.

N: Listening to your story I was thinking about what that constant state of “otherness” must have been like for you, in both Iraq and Iowa.

U: I do think that where you’re from and what is going on politically with the United States has an impact on how you see yourself and how you grow up. Japanese Americans during World War 2 had a very different experience as opposed to being Japanese American right now. It’s loosely comparable historically to what happened in the 70’s with Arab Americans, because of tensions with Iran, but the American concept of “Arab” was still the oriental carpet, the genies and riches. Back then things were kind of mild.

Later on, with the Gulf War and the way it vilified Saddam Hussein, and then of course post 9/11, I can tell, it’s in the air.

Not having the legal definition of “who you are” also kind of effects you. I was kind of in this nowhere zone for awhile. When I was living in Iowa City I used to work at this restaurant as a dishwasher, of course, and my boss was actually from Algeria. He had this thick accent, his English wasn’t great but he was losing his Arabic- He was in this limbo. He didn’t quite completely have the English language down, but he had completely lost the Arabic language. In a way you do choose it, or it chooses you- like one pulls you further. I really truly do think I’m an American, but that’s not in opposition to anything else. Of course it would be difficult for me to go back to certain countries in the Middle East and fit in, but I’m okay with not fitting in. And really, there are other people like me. I definitely feel like a contemporary citizen in that I have this duality, and I think it will be more common. People can grow up in multiple cultures. It’s no longer “I was born in this town and grew up in this town and I’m going to die in this town”.

N: It’s not really possible so much anymore is it? We have the entire world at our fingertips.

U: Also, often people who come from countries that are in conflict are spread all over the world, because you can’t go back.

N: I do want to talk about Baghdad, Iowa as a film and as a concept. You talk about being of two places. People often search for a home, in many different ways. In many ways you identify as an American, but also it seems as you lived through these various states of flux you found a home within an imaginary space, that within your imagination there was a constant place for you.

U: Absolutely, yeah.

N: Bagdad, Iowa, as you have said, is an imaginary place that you are “circling closer and closer to”, as if you are being pulled. I think this concept of places having a psychic gravity is quite interesting. What is the pull of Iowa for you, on a real or symbolic level?

U: I think the gravity of the place is very much connected to the earth, and growing up there. There is something very truthful and important there, our experience there as a family and who I was and my friendships. Everything I experienced there connected me to the land. I hear some of my relatives in Palestine talk about missing our homeland, or Iraqis who cannot go back to Baghdad and the love they have of their land, but wherever they are, they can bring it. They make the same food, the have the same friends around them, they are listening to their favorite music. That is a kind of a conceptual experience you can take almost anywhere. So, I was kind of still growing up in the Middle East in a way, even though I was in Iowa. We would go to mosque and surround ourselves with other Arab families. There is this common experience even though we are not necessarily in our native land. It’s a new experience and a unique fit, and it’s not necessarily based on the strategies of a lot of the European settlers. It’s a new idea of what this land could be. I didn’t realize that until much later.

Also, I grew up not completely having a solid home, so things like my movies and books, my family, wherever we took that, it was home. So really I’m expanding that into something that can be a place itself. That can exist because, in a way, I willed it to. It’s funny how you put it, the gravity of it pulls these scenes and visuals and words from me that I’m reflecting back to it. And it absolutely becomes this very specific thing. Even when I talk to people about it, it’s almost like it is a real thing. You can do a Google search for Baghdad, Iowa and it has become a real place. At one point, I remember my daughter was asked “where is your dad from?” and she said “Baghdad, Iowa”. I make films, studied art a little bit, I love the idea of art making as process- but I love the idea of it being connected to something real, even if it is conceptual. So absolutely it speaks from a real place. It’s all these experiences connected. It is something unified. Maybe earlier on it was a bit more abstract but now becoming more literal. I have clothing from the natives of Baghdad, Iowa that has been made I have started to collect recipes of Baghdad, Iowa. I have profiles of these subjects. Even though the film is going to be very fleeting, I’m developing real people. That’s definitely pulling me into the gravity of the film. I am getting closer to it.

N: I wanted to ask you about the young man who assaulted you in Iowa. How do you consider that event in relation to Baghdad, Iowa?

U: I think that I’ve taken aspects of the violence that happened to me and made it almost collective. I’ve taken a lot of things that I have seen around me, incorporated things that can happen in Iowa, young men that have a lot of rage and find someone vulnerable. It can also be young men with guns at checkpoints in Iraq. What actually happened to me has informed it, there is that position in there of that violence, of that assault. And I think that violence is always going to recur in some way. What happened to me is a big part of the film, and in a way it is almost repeated. I reenact it, fictionalize it.

I think a lot of this project, Baghdad, Iowa, is a way for me to try and figure out all of this that has been going on in me. An internal psychic process that’s being reflected, being projected, with film, with images and words. Perhaps trying to make some sense of that chaos. In a way making it more poetic, maybe trying to grasp something with it. I’m not entirely aware of how it is being processed, but I’m aware that I’m using how I felt being traumatized, being afraid.

There are also elements of what turns me on, what’s mysterious to me, that are driving the film as well. I had been thinking about it, through all of my experiences growing up in Iowa, and they were really profound. The assault on me was another profound experience in it’s own way, and I guess at this particular time I’m not interested in making a moral statement about it. I just want to keep this experience, and maybe in a way when I objectify what happened to me to look outside of it, it’s more interesting than being inside of it and being a victim of it. It’s the way I work. I’m able to pull out and I’m no longer who I am so much as part of this larger construction, the movement, the emotions and people having to deal with each other in this state. So I begin to better see myself that way.

—

Usama Alshaibi currently makes his home in Boulder, Colorado with his wife Kristie and daughter Muneera. Baghdad, Iowa was completed on June 29th, 2015. Upcoming screenings include the Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur, the short film festival of Switzerland, with more to be announced soon.

Excerpts from Usama’s notebook for Baghdad, Iowa (featuring drawings, collage, and a short story) will be featured in MIDWASTE, a forthcoming publication.

Alshaibi also speaks of a “total demonization of the Iraqis.” As Kyle’s platoon is invited by an Iraqi Eid feasts after they stormed his house, the hosts turned out to be deceitful and evil, he has in the next room a weapons cache hidden under a steel plate. ““Even the great Iraqi and Arab tradition of hospitality is degraded,” says Alshaibi.

I was interviewed in Germany’s newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung about American Sniper.

Check it out.

PDF copy in German: SZ150217_p10

I’m really happy to be on this list. I know many of these fine talented folks and honored to be included with you all. I’m number 21!

From Film 50, 2014: Chicago’s Screen Gems:

Usama Alshaibi is studying for his MFA in the “mellow college town” of Boulder, Colorado, along with the likes of filmmakers Phil Solomon and Alex Cox, but the director of “Nice Bombs” and “Muhammad and Jane” is still in the midst of promoting his fine, fierce long-in-the-making family history “American Arab.” “Oh man,” he says when asked about any lessons from its ongoing release. “Identity is fluid and Arabs are still having a tough time in America. But, I also learned that I am comfortable in my own skin. I don’t need to apologize or answer to anyone.” While Alshaibi’s experimental shorts and features can readily be described as transgressive, his current work, co-produced with Kartemquin, earns that label in its own right. “Every time the United States bombs Iraq, it triggers these impulses in me. Of course these triggers have always been there, and much of my early work came from that primal place. There has to be some desire, some rage, some passion that makes me want to pick up the camera and start creating something. I never saw there being a line between my more experimental, transgressive work and the documentaries. A real Muslim Imam in Iowa and his story, in contrast to a fictional Muslim sex worker in Chicago—both of these narratives are interesting to me. In one, I may take a more straightforward approach and, on the other side, I can let go and dive into a psychedelic realm. I can explore moods and tones, something more poetic. I’m comfortable with being called a transgressive filmmaker. It’s who I am. I’ll wear that badge with honor.” Alshaibi’s current projects include “Baghdad, Iowa,” “my nightmare-love project. A fictional home. A place that cannot be found but is. It’s based in real events but dipped in LSD and death.” And Usama and his filmmaker wife Kristie are working on a doc called “American Dominatrix.” Still, despite the identity issues his work is steeped in, Chicago is key. “I would not be who I am today without Chicago. I’ve made life-long friendships in Chicago. From my days at Columbia College to the Chicago History Museum and Chicago Public Radio and my cinema family at Kartemquin Films. And of course the community around the Chicago Underground Film Festival. We all have our tough days in Chitown, but it is the city where I met my wife and really figured out how to live and make it. Chicago lives in my blood.” – See more at:http://newcityfilm.com/2014/10/02/film-50-2014-chicagos-screen-gems/3/

The Film Yap: “American Arab” is obviously a very personal film; can you tell us how you got started on this project and what your vision for it was at that time?

Alshaibi: I was noticing that there was this rising hate and hostility toward Arabs and Muslims in the United States and it was typically based on racists ideas– so I wanted to make a film that exposed these racist sentiments and also exposed who Arab Americans really are. The United States of America is home to almost 4 million Arab-Americans that are very much part of the fabric of this country. But the media and the movies in the United States depict us like crazed, inhuman terrorists. Those depictions make it easier for Americans to dehumanize us and bomb our homelands. I’m saying Arabs are not only part of the United States but we are part of the formation of America. Can you imagine the United States without Casey Kassim, Ralph Nader, Danny Thomas or even Steve Jobs? All of them are Arab Americans. So I wanted to talk about that, but also tell the human story of who we are. Like Amal Abusumayah in my film. She was born in Chicago and raised by Palestinian parents. She has the right to live freely and wear her hijab if she wants to. That is her right as an American. So when a bigot tries to pull off her head scarf and tell her to go back to where she came from, that is the dark spot of America I’m discussing. Every Arab in the United States has experienced this type of harassment and racism in the United States and we are sick of it.

One of the challenges for a documentary filmmaker is adapting to the story as it evolves and goes in unexpected directions. What would you say was the most surprising development over the course of this project?

Alshaibi: When I started the project, I was mainly focused on other people and wanted my own personal story to be more of a secondary narrative. But life moves on even if you are working on a documentary. I moved away from Chicago and had a baby girl with my wife in Iowa; these elements became part of the narrative of the film. My story became part of the bigger story. And I’m OK with that. In a way, it was easier for me to show more of my life and be very open about it.

What is your favorite memory from working on “American Arab?”

Alshaibi: My favorite memory is part of my life and the film: That would be the birth of my daughter, Muneera.

You’ve described this film as a “Coming of Arab story” and, as it shows, much of the Arab American experience is influenced by events in the Middle East. With the increasing violence in the region given the Syrian Civil War and the withdrawal of U.S. troops in Iraq, what are your thoughts on how this will influence the “Coming of Arab story” of the next generation of Arab Americans depicted in your film, such as the young Jassar girls or your own daughter?

Alshaibi: Well, the younger generation needs to know what we went through as Arabs in America. They need to understand that after the attacks on the Twin Towers, that Arabs and Muslims were targeted, questioned, put in jails and abused. Hate crimes went up, and the media and the general American population was indifferent to it. So they need to see this and realize that the United States is their country and to speak out and be vocal about injustice. I want the younger generation to realize that they have a right to be angry. They have a right to speak up and speak out for their human rights and dignity.

Alshaibi (far left) in American Arab

Last night the 21st Chicago Underground Film Festival closed with Usama Alshaibi’s American Arab, a documentary profile of various Arab immigrants and the American-born children of Arab parents. It’s the former Chicagoan’s second personal documentary (after Nice Bombs, from 2006), as well as the least confrontational work this longtime provocateur has made. (For more on his development, check out the conversation we posted last week between Alshaibi and local filmmaker Carlos Jiménez Flores.) Where his other movies have played in underground film festivals, Alshaibi hopes for American Arab to screen in community centers and high school classrooms. I spoke with Alshaibi last week to learn how changes in venue and the makeup of his audience shape how he regards his movies. Our conversation soon turned to spectatorship in general, as we discussed, on the one hand, how movie audiences can provide independent filmmakers with a sense of community and, on the other, how audiences assimilate images in mainstream entertainment.

Ben Sachs: How many pieces have you presented at CUFF at this point?

Usama Alshaibi: My first thing at CUFF was a music video I showed in the late 90s. The following year, I made a short film called Dance Habibi Dance. That was sort of my breakout—I made it immediately after I finished at Columbia College. I’ve premiered all my other features and a lot of my shorts there. It became a home for me, a place where I knew people would be receptive to what I was doing. The screenings are awesome, the parties are fabulous. So it’s a place I want to keep coming back to. [It’s] close to my sensibilities.

That makes sense. Your narrative movies often deal with subcultural communities.

When I decided to get into film, I was inspired by the cinema of transgression. I liked the stuff that Richard Kern was doing in New York, also Nick Zedd and Lydia Lunch. I would reach for these underground films . . . but at Columbia, there was a push to make more conventional types of films. I remember visiting film crews and being turned off and overwhelmed by the amount of people. It seemed like too much for me. I liked just having a camera and a couple actors, having the crew act in the movie. That’s just who I am, and the festival reflects that.

You made American Arab with Kartemquin Films. This has got to be the most mainstream thing you’ve done, no?

It is. It’s a big leap from my last feature film, Profane. Have you seen that?

I reviewed that when it played at CUFF a few years ago.

That’s right. You called it a bargain-basement version of Enter the Void, which I really appreciated. That was a high compliment to me.

I was afraid you’d take it as an insult.

No, no! Enter the Void cost so much money, but you thought we were able to get at the same stuff for very little! I funded the whole thing, I shot it, I did everything. Later it won the best feature prize at the Boston Underground Film Festival—which just rejected American Arab, incidentally. So you’re right—it is a more mainstream film.

As for Kartemquin, I’ve always admired them. One of the first movies I saw when I came to Chicago was Hoop Dreams, and I was blown away by it. I remember bumping into [Kartemquin cofounder] Gordon Quinn in the South Loop when he was shooting The New Americans. I just went up to him and said, “Hey, I want to talk to you.” That was pretty much my only interaction with him before making American Arab. [laughs]

I knew that I was working with Kartemquin and that they have a particular philosophy about filmmaking. They have a clear idea of social practice, connection to the community, and how films can help people. These are very noble goals, so it was an honor to attach myself to an organization like that. Now, you said this was a mainstream film . . .

In that you made it with a more professional production outfit than you usually work with.

That’s definitely true. I think that professional filmmakers have to cast a wide net with certain films. I can make art films and know that there’s a specific audience for it. But this movie is something I want everybody and their neighbor to see. The message is large, and it’s clear. So I think that was the important thing with this, being able to communicate clearly. Because I do think it’s getting at something important.

It’s giving voice to people who have been marginalized—and when they are presented in mainstream American media, it’s rarely from their perspective. Also since 9/11, bigotry towards Arabs has increased noticeably in this country. Certainly that’s influenced depictions of Arabs in the media—regardless of whether the depiction is positive or negative, it’s still responding to the zeitgeist.

I agree that things changed after 9/11 and that fear and paranoia regarding Arabs got pumped up. But, as I argue in the film, that had existed before, just in a different form. When I was a kid, it was typical orientalist stuff—that we have flying carpets and camels and all this stuff.

You have that montage in American Arab of stereotypical Arabs in Hollywood movies, mainly from the 70s and 80s.

The big one was Back to the Future, because that’s a great, iconic film. I was a teenager in the 80s, and I saw it in a theater. I liked the film, but . . . every time I’d watch films with friends and these scenes came up with crazy, hysterical, terrorist Arabs, I’d cringe in my seat. I’d try to block them out of the films in my head, but they were always there.

These things affect people. As much as we might want to deny it, when conventional, Hollywood movies keep giving us these images of bad-guy Arabs, they get normalized. So when a crime is committed by an Arab [in real life], all those images come back to people, because they’ve seen nothing else. They don’t think of Steve Jobs when they hear about an Arab-American—they think of the wild, bearded guy with a turban and a gun.

One of the things I’m doing [in American Arab] is pointing out this way of thinking about minorities in America. Every minority group or ethnic group has been subject to it, and I want to point out that it’s happening again. We need to call it out when we see it.

At the same time, the movie doesn’t feel confrontational. It feels like the start of a conversation, rather than a provocation. I was a little surprised by that, actually, having seen some of your other movies.

If someone in the audience is on the fence about Arab-Americans and my movie pisses him off, then I don’t think the movie is successful. And yeah, I’ve made a lot of provocative shorts and things that are a little more aggressive, but I’m not really interested in that anymore. There are discussions that take place within the Arab community, and then there’s a greater conversation [in American society]. I’m trying to bring these two together—you know, going in the Kartemquin spirit of [starting] dialogue.

Do you say you’re not interested in provoking an audience with regards to this movie or that you’re done with that indefinitely?

Well, I don’t necessarily try to make transgressive cinema—it’s just in my blood. [laughs] I have certain obsessions and dreams and nightmares that I keep returning to. But with this film, there’s a little more of a social message. There’s also a diary element and humor and documentary elements . . . I look at it as a way to introduce people whom I admire [to audiences].

A lot of the people in American Arab remind me of my family or my friends or even myself. And I think about young people growing up [in America] now who are refugees from Iraq, Syria, or other Middle Eastern countries . . . I’m hoping they can catch this film and not feel so alone. That’s why I want to make it as “rated G” as possible—well, maybe not G-rated, because there’s a lot of swearing. But I was thinking of this as something that could be shown in high schools and community centers. I want other young [Arab-Americans] out there to see it and know that they’re OK. There’s a lot of hate being thrown at them because of who they are or where they come from, and I’m saying, “Don’t worry about it. You can be yourself in America. That isAmerica.”

Do you see yourself making more movies that could be shown in community centers?

Probably not. I’m interested in these themes, but I pretty much make the kinds of films that I like. And a film like Profane, I’m not going to bother showing that to a certain community—it’s not going to be helpful to them. But that movie was something I really wanted to do. And so, it’s played at sex workers’ film festivals [festivals of films by and about sex workers] and underground film festivals.

This documentary was unique for me in that it was a collaboration with Kartemquin. If I make another movie with them, it will probably resemble this. But for now, I’m happy with it. It’s the big statement.

By Ben Sachs (Monday, April 7, 2014)

source: http://www.chicagoreader.com/Bleader/archives/2014/04/07/watching-the-audience-with-usama-alshaibi

“What it means to be American needs to be reexamined.”

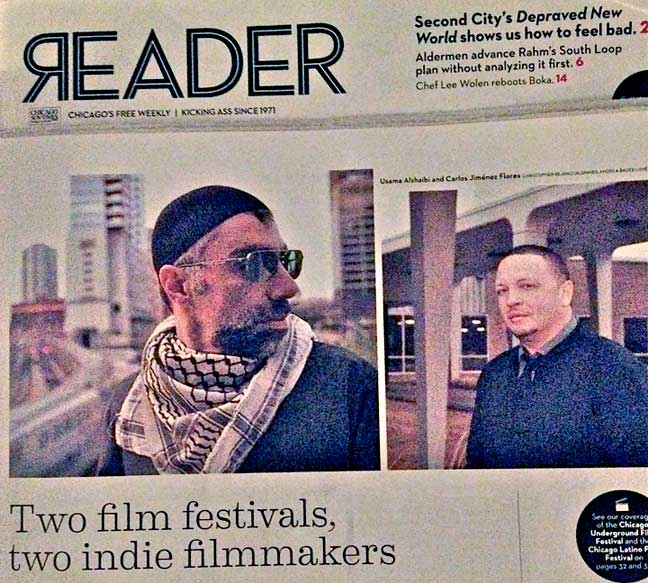

Two film festivals, two indie filmmakers, one discussion on filmmaking ethics.

Usama Alshaibi and Carlos Jiménez Flores have different filmmaking styles, but they take a similar stance on mainstream depictions of race and ethnicity in popular media.

It’s officially film festival season in Chicago. As the Gene Siskel Film Center’s long-running European Union Film Festival wraps up, two similarly enduring fests, the Chicago Underground Film Festival and the Chicago Latino Film Festival, are shifting into gear this week. Though they offer wildly different programming—CLFF favors narrative features, CUFF prides itself on experimental fare—both festivals make it a priority to promote small, independent voices. Closing this year’s CUFF is American Arab, a documentary directed by former Chicagoan and Columbia College alum Usama Alshaibi and produced by Chicago’s venerable Kartemquin Films. Incorporating his own experiences as an Iraqi-American with those of Arabs across the country, Alshaibi explores the post-9/11 struggles and contradictions of Arab identities.

For this interview, Alshaibi talked with Carlos Jiménez Flores, a local Puerto Rican filmmaker whose deeply personal feature My Princess, a black-and-white drama shot and produced here, is featured in CLFF’s “Made in Chicago” segment. Like Alshaibi, Flores takes stock of race and ethnic issues, particularly those pertaining to his own community. The two filmmakers didn’t know one another prior to their conversation, but they quickly found common ground in their positions on the ethics of filmmaking and the narrow portrayals of race in media, and their deep connections to their respective backgrounds. —Drew Hunt

USAMA ALSHAIBI: So Carlos, did you study film in Chicago?

CARLOS JIMÉNEZ FLORES: My degree is in human resource development and sociology. I didn’t want to study film. Basically, I’m a storyteller, so I thought human resource development and sociology would give me the depth to tell a better story. I started out as a producer, and always figured I could hire the people who went to film school. Eventually I transitioned to writing and directing.

UA: When I went to Columbia—this was in the mid- to late 90s—there was a real push from the school to work on Hollywood-style film sets. Some of my peers were moving to LA and working on union shoots. I had been to a couple of really massive shoots where there’s a crew of 40 people, but it really turned me off. I just didn’t want to make those kinds of films. When I left Columbia I started to make really small films—just me and a camera and another person. That kind of filmmaking is what I really loved.

CJF: I find it fascinating that you were turned off by being on set with 40 people. That’s how I started, but when I began to shoot my own films I had six to ten people. I’ve been on big-budget sets with big crews, and it’s a little overwhelming.

UA: I totally agree. Even as I started making bigger films, I’ve always kept my crews small.

CJF: The bigger the crew, the less spontaneity you have. With a smaller crew I can say, “Hey, I just thought of something—let’s move this and go somewhere else and shoot a different scene.”

UA: I think what happens in filmmaking is a young person will go on a set, and whatever set they walk onto, that tone becomes what filmmaking is to them. But there are so many different ways of making cinema. When I was starting out everything was celluloid. But I was actually embracing video pretty early on. I really admired the Dogme 95 movement and seeing what was possible with digital video. For one of my early features, Muhammad and Jane, I shot the whole thing on digital video. It was kind of a love story, but it also had to do with the politics of the time around 9/11 and how Arabs were treated and how foreigners were treated. And like your film, My Princessa, I actually shot it in black-and-white because I was interested in contrast. But I remember folks saying, “What kind of film stock did you use?” I’d go, “It’s on video,” and they’d just kind of walk away—which is silly now because so much is shot on video. I think the idea is not to get so consumed with [format] but to remember that the tools we use—film or video or whatever—help tell a story. It doesn’t really matter what you shoot it on.

CJF: Someone can tell an incredible story using an iPhone. I want to ask you some questions about American Arab. I’m Puerto Rican, and Puerto Ricans in the United States are grouped into all these other countries that also speak Spanish. So we’re labeled either Latino or Hispanic. There are debates whether these terms are acceptable or not. So my question is about the word “Arab”—I’m not sure if it’s the proper label over something like “Middle Eastern.”

UA: It’s an acceptable word, but it’s also used to demean. I mean, you can call someone a Jew and say it in a way that’s derogatory. Most Arabs in America would call themselves Arab-Americans, but my film’s title, American Arab, signifies identity. It’s also about process and transition and realizing that the question of identity is very interesting. When I was interviewing Arab- Americans, some of the younger people didn’t identify themselves as white, but some of their parents identified as white. Immigrants who came here in the 50s, 60s, and even the 70s were “white”—unless they were black. If you came from a Middle Eastern country, you were white. Now there’s more of a sense of a brown identity, and people want to be more specific about what they are. I think within ethnicities there are certain complexities, but from a white American perspective people are lumped in these gigantic categories. I’m sure you get lumped. I get lumped constantly. And then we’re cross-lumped. Mexicans or Puerto Ricans are often mistaken for Arabs, and all the hatred and vilification that comes with [the mistaken identity] is attributed to [the target], regardless if they’re from Baghdad or Mexico City. That’s another thing I talk about in the film.

CJF: These themes creep into my work, too, though not directly in [My Princess]. It’s weird because the media in Latin American countries and Puerto Rico, as well, have bought into the views of the United States. They tend to keep lighter-skinned individuals in front of the camera, and I don’t care for that. The reality is we’re all different shades, so in My Princess and in my movies in general, I cast according to talent, not according to looks. I aimed to illustrate all the beautiful skin colors in My Princess, even though it is in black-and-white. I’ve always wanted to make a black-and-white [film] because it’s romantic, a character within itself, but you see the beauty in all the shades.

UA: That’s, in itself, is a type of political statement. And what you say about light skin—it’s not just Puerto Rico. All those skin-lightening products—it’s a huge multimillion-dollar business.

CJF: All of this just reiterates that struggles over identity are universal. The theme of your film connects with me. We need this type of discourse because it will help break down the barriers that have been built over generations.

UA: Absolutely. I think the United States is starting to see the melting pot happen right now. As the landscape of America is changing, this type of conversation becomes more important and relevant. People need to be able to feel like they’re complicated. It’s not like there needs to be any tension between you being an American and you being a Puerto Rican. In another way, you can also say, “I abandon both of these cultures,” and sort of find your own. One of the people I talk to in the film—his name is Marwan Kamel, his mom’s from Poland and his dad’s from Syria, and he said something very beautiful and simple: “Allow people the ability to be complex, give them that space to be complex.” It’s important to allow these stories to be heard, and I think certain filmmakers who have been marginalized in the past also need to be heard. I think what I get from your film is it’s not a simple story, there are a lot of layers and it keeps changing, it’s not fixed.

CJF: I was born in Chicago, but when I was a toddler my family moved back to Puerto Rico. I had no idea I was from Chicago, and didn’t speak any English until I was eight years old. Coming back here, I got an idea of the melting pot idea, [but] I didn’t see it as a melting pot; I was experiencing a lot of prejudice and racism. My father, who was dark-skinned, also dealt with a lot of racism. I saw how he was treated and suffered. When my parents divorced, he went back to Puerto Rico and never came back to the United States. So I started to question whether America was a melting pot. To me it seemed more like a salad, where nothing is blending; it’s just all these ingredients bouncing around this bowl. I agree with you that things are becoming more of a melting pot. I find it amusing that there are people whose families have been here for four, five, six generations—they don’t get that they came from somewhere else. I see how they treat people who just got here like crap, and I wonder what their grandparents or great-grandparents would think.

UA: And it’s not that long ago. For a lot of people, it’s their grandmother or great-grandmother who came here. You and I are the same age. I also was a kid in America in the late 70s, and you’re right, it was tough. Just having black hair was radical. And my father did the same thing as yours: He never quite felt settled here and went back to the Middle East. My mom stayed here, but my father has never really come back. Our stories are common.

CJF: I think films like yours are starting to tackle these problems. We need to break down those walls and start making films that are more inclusive. We need to make films where the bad guys aren’t the same kinds of people each and every time. The media has a huge influence on how people develop these ideas. Most of the things you see onscreen are not real, yet we see it day in and day out, and it becomes the truth. It’s hard to make it in filmmaking, but once you do it’s time to start breaking down the doors—or jump in through the window or come in through the back door. It’s our responsibility as filmmakers to say, “Here’s a different take.” Hopefully we get enough people to come on board and maybe things will start to balance out.

UA: You’re absolutely right. It’s our responsibility to change the visual landscape. The people who are making these Hollywood films have a cartoonish conception of what a Puerto Rican is and what an Arab is. They put the simplest two-dimensional character on the screen, another movie copies it, and they become cookie cutters. We have to beat that down and mock it for what it is. Like, can you imagine if someone did blackface now? They would be laughed at. But at one point that was an acceptable form of entertainment. Hollywood uses brown-face now—Mexicans and Latin Americans are consistently used to play Arabs in Hollywood. Our responsibility is to get in there, talk about this stuff, and change what beauty is—and change what a leading character can be. What it means to be American needs to be reexamined.