BAGHDAD, IOWA

Sections of this essay came from my MFA Thesis

from the University of Colorado Boulder

Written by Usama Alshaibi (2015)

The project Baghdad, Iowa has various manifestations, which include a film, photos, a journal, as well as relics and objects that act as motifs that can encompass both the personal and the conceptual.

The framework constructed under the concept of Baghdad, Iowa; which acts as a conceptual apparatus that produces art and media. The film, objects, and artwork connected to Baghdad, Iowa are all manifestations of this concept. They take on their own appearance, depending on the medium they travel through.

This liminal landscape, artificial yet grounded in a personal cultural mash-up of memory and pain, is seen through the camera, or the windshield as screen, as an attempt to reach a border between the seen and unseen. The town Baghdad, Iowa, is an imagined place that is transitional and conceptual. It is a place that connects my personal memories and trauma to an artistic space, which in turn allows both fears and desires to be expressed. The 34-minute film Baghdad, Iowa, is the most complex system in this expression, but the other works also have autonomy and connected narratives. The exhibition or film is one way to view the construct of Baghdad, Iowa. This hybrid concept can be expressed and evolved in many forms.

The aim of this essay is to clarify how the conceptual mechanics of this apparatus can be assembled. There are emotional components connected to growing up between Iowa and Iraq that are pulled from my memory. These components, and the early death of my brother, compose the larger wheel inside a metaphoric golden watch moving us forward. Trauma, recovery and the restless traveler are the themes expressed here in a type of augmented reality through a common formula: Baghdad, Iowa.

I. The Origin.

The creation of Baghdad, Iowa was triggered in part by wanting to find something poetic in the unknown. I started constructing a place that could reference moments in my life growing up displaced between the Midwest and the Middle East. This subtle idea was also compounded by the death of my younger brother, Samer Alshaibi, a devout Muslim, a drug addict and writer who died at the age of 28. I wanted to create art and meaning, and seek a recovery of sorts, from the dark story of my brother’s downfall. I was also affected and inspired by returning to Baghdad in early 2004, and seeing my homeland devastated by the United States’ invasion. I thought going back to Iowa would help me as I navigated this unstable landscape through winding roads and the screen of a car windshield.

I wanted to live inside a suspension of disbelief, motivated in part by a romantic notion of what was possible, on the road through the night journey – the ability of cinema and art to create an augmentation of reality.

I wrote down Baghdad, Iowa in an art journal and suddenly something opened up in my imagination and my senses. It was a kind of portal within my own construction that created images and words connecting me to this augmented reality.

Baghdad.

Baghdad, in Persian means “the gift or garden of god.”1 It is my birth home – the place where I first opened my eyes and felt the heat and the saw the loving faces of my many family members. On the streets of Kadhimiya, with the horses and carriages, and grilled lamb mixed in the air with the dark teas and the aroma of cars, grease, cumin and fire, my father took me to a place where a man carved my name into a golden ring. Kadhimiya is home to the tomb of two of the Shia saints, meaning “those who swallow their anger.” The double golden domes glow like a pagan Babylonian goddess – her shiny breasts emerging from the earth. Inside the holy mosque, you can see the tombs and the mourners in black weeping dramatically. The loud speakers sing melancholy prayers, and kabobs grill in the summer dust, as the bare colored lights and the cardamom sweets swim in the night. Even the djinns are out – spirits made of smokeless fire that both guide and misguide the human race. The bread is flat and still hot. You need gamar and dibis for this. The gamar is made from ox milk and the dibis is the syrup of the date trees that grow all over Iraq. There is noting like it.

My grandfather would show me his garden, and I remember the green grapes and the walking sticks hiding in the branches. We always had fruit and fresh bread, cheese, tomatoes, cucumber – and at the night the large boxed television tube would slowly come on, expanding from a tiny white dot into a waking illuminated glow. There was always tension when the news came on – like a final warning as the men and women smoked and drank dark coffee in little glasses. The state was always in crisis. The floors were marble and the walls lined with fluorescent lights and framed pictures of my Uncles and Aunts with their diplomas and graduation caps. But I also remember my grandfather taking one of those portraits down, and smashing his foot into it and shattering the glass. We don’t speak of this incident. This is my consumption. These are my early years as a human, a child being raised in Baghdad. The history of this city is our human history. It’s where it all began – the birth of civilization – and it’s steeped in fantasy and brutality. I was literally kidnapped by my grandmother a few days after I was born. She wrapped me in her black abaya and tried to leave the hospital. I was recovered and brought back to my mother. But I’m reminded of this story- the story of my birth.

After that it was Iowa City and then back to southern Iraq. I was in Basrah during the Iraq and Iran war – the darkest and most traumatic period of my childhood. Every night the bombs were dropped and every night I would be ready to die. There I found the bullet casing in front of our house. I had many of them.

Later in Iowa City, I would see Baghdad in movies: Sinbad, Aladdin, the flying carpets, mythical creatures, “Open Sesame,” and this magical city glowing with blue-eyed actors smiling and waving. This stayed inside of me, a thousand and one bombs, my city, my birth home, always moving and never still – a place of reality and fantasy.

Baghdad, the concept, my idea of it, becomes a component into this construction.

Iowa.

I also grew up in the smart college town of Iowa City, Iowa. I would call it my hometown. When we were away from Iowa, I missed it and wanted to return. In Saudi Arabia I would consume American television through Betamax tapes. I even watched the commercials with longing. These recorded American television shows were almost enough to conjure up the feeling of being back in Iowa for my sisters and I. Eventually we did return to Iowa City, and my father stayed in Middle East in order to work and support us.

I had a well-rounded and liberal education in Iowa City. I graduated from high school there and came of age as a young man. I discovered punk, counter-culture, art, literature and LSD. My parents also divorced during this time. It was my most wild time as a young man. I took many risks and had a manic and fatalistic view of the world. I survived on my own washing dishes. I had no legal document to work in the United States, so I just survived doing unskilled labor, mostly in kitchens. I traveled to San Francisco and even lived in Boulder on my own when I was 18. I tried MDMA, or ecstasy as it was called in the late 80’s. I have no romantic notion of drug-use. I’ve been in difficult mental places on various chemicals that I regret. Heroin and cocaine killed my brother. But I think it’s important to make a distinction between a drug like Lysergic acid diethylamide, and a narcotic. LSD did change my perception of what was possible in traveling through time and space. It wasn’t always a pleasant experience. But I felt like I witnessed an inner and outer Universe that was larger than me.

The land that connected me to that psychedelic experience was in the fields of Iowa. The cornstalks, the humid summer nights, the crickets, wet grass and the dark skies with stars left an impression on me. Those dirt roads in Iowa could lead you into mysterious landscape that was not always on the map. It was my America. The only one I knew to be true. It was all there in front of me.

The word Iowa comes from Sioux Indian word ayuhwa, “to be asleep,”² the sleepy ones. This is the name of the Native tribes that resided there, but through the eyes of another tribe as told to the European explores. This was a problem for the names of many Native tribes in the region; they were simply given names that did not correspond to what they called themselves. The name of the state of Iowa has been attributed to the Ioway tribe, even though they have been relocated in 1837 to reservations along the Kansas-Nebraska border. Like all the histories of colonization and stealing of native lands, there is chaos and destruction. I have no direct connection to Native Americans, mine is merely the recognition of the name and its own story of displacement of another people. There might be indirect connections with the tribal women in hijabs and abayas, and the masks and weapons may be speaking to the ghosts of the Native tribes. But those are details that have emerged organically. The real story of Iowa is my Iowa, by way of Baghdad. In its small way, it became a magical place for me as child.

But I was still the outsider looking in. Where did I come from and where did I belong? These are the questions I would ask myself growing up.

Samer.

On May 1st, the summer of 2006, my 28-year-old brother died from an overdose of heroin and cocaine. My family was devastated, especially my mother. She had brought us to the United States to be safe and she lost her son at a young age. Our brother Samer, was the first one that was born in the United States – in Iowa. He was hope. He had a U.S. passport. My sisters and I were born in Iraq and would have to wait years and go through an array of immigration dances, and in my case political asylum, to finally get our citizenship. One of the hardest aspects of losing a loved one is also dealing with all the logistics of death. There was a Muslim man living in Chicago many years ago and had also lost his son at a young age. He noticed there were no burial sites for Muslims; so he bought land at a cemetery just outside of Chicago, specifically for Muslims. This is where we buried my brother. This is also the moment I finally stepped away from Islam. I remember the Imam telling the women to step further away from the his body before burial – the women were not allowed to be close to Samer according to this Imam, this religious leader. But I openly disagreed with him and asked my mother, my sister and my Aunt to come near. These were the women who had raised my brother.

The Muslim body, after it is wrapped in the traditional white cotton, becomes a type of universal object. The fabric bounds the body so tightly it seems swaddled like a baby. But these details aside – what matters in relation to my project is the tombstone. In order to finish the tombstone, my mother was asked what country my brother was born in. She simply said, “Iraq.” I asked her why she said Iraq when Samer was actually born in Iowa. My mother very calmly said, “that is what he wanted.” And there it was, Baghdad, Iowa, fibbed into existence. It was created by sincerity and fiction, with some deeper truth, but not factual.

When it came time to bury him I helped dig the grave and place dirt over him. Again, these snapshots of the past and these rituals play into the narrative-fiction in a stylized way. In some places it is specific, and others more abstracted. Nature and artificiality merge through the story of Baghdad, Iowa.

So why did my mother change his place of birth? I believe my mother wanted to honor him, to give him a gift posthumously. As Samer grew older, his American status was not so cool anymore. You want to be a tough guy? Tell them that you’re from Iraq. That could have been one intention, but I also think it made him feel connected to his culture, which he rarely saw, or felt. But when my mother had infused reality and fiction into his birthplace, it gave me this idea. She wasn’t lying but she was also not telling the truth. It doesn’t matter. But at that moment I thought: Baghdad, Iowa is also a place of transition, a place that can exist conceptually to help in understanding the invisible, the unknowable, even death. Her gesture, after death, was meant to help both herself and him.

So why did my mother change his place of birth? I believe my mother wanted to honor him, to give him a gift posthumously. As Samer grew older, his American status was not so cool anymore. You want to be a tough guy? Tell them that you’re from Iraq. That could have been one intention, but I also think it made him feel connected to his culture, which he rarely saw, or felt. But when my mother had infused reality and fiction into his birthplace, it gave me this idea. She wasn’t lying but she was also not telling the truth. It doesn’t matter. But at that moment I thought: Baghdad, Iowa is also a place of transition, a place that can exist conceptually to help in understanding the invisible, the unknowable, even death. Her gesture, after death, was meant to help both herself and him.

My brother’s death almost destroyed me. I knew when I was summoned to the hospital that something was wrong. A police officer led me into a back room and the first person I saw was a priest. They told me his body was in a small room and that I could visit him. They offered me a cup of water. I drank it. I remember touching his body and he was cold, but not stiff. I could still sense him in the room. I could feel him leaving.

I knew about the drug addiction and I tried to help him before he died. I also had my own drug problems at the time: speed, booze and anything else that came my way. These detailed struggles become part of the narrative for Baghdad, Iowa. I conjure up part of my brother’s humor, his addiction, his embracement of pleasure, of joy and the instability of living within an immigrant family. He was our first generation American and he died in front of our eyes.

He was dead and I had to do something. Samer’s fabricated tombstone, created in part by our mother, is in itself a stronger and more telling truth. Even though it’s factually wrong. He was born in Iowa, but now he was born in Iraq. It’s not just about his identity; it’s about a narrative that can be written with healing intentions. And in that process, something new is created, an object with a story. It has charge. It has a story by its very presence. Objects can have meanings if we infuse them with these desires through trauma or pain.

The watch.

The watch belonged to my father, Hameed. He never actually gave it to me. It was a golden watch that I always associated with my father. I used to hold his hand in our many journeys through busy streets with crowded bodies. It was reassuring to see his hairy arm and the golden watch ticking in front of me. I knew it was my father. This color, the bronze-gold, it reflects the corn fields of Iowa, the golden domes of the mosques in Baghdad, the sand, the yellow brick road into all the madness and magic of Baghdad, Iowa.

Can this watch be contained like a memory, a recording, preserved artificially and considered a ‘thing’? In Susan Pollack’s essay “The Rolling Pin,” she talks with great affection about her late grandmother’s rolling pin when she says: ‘I think of the hundred of pies and cookies it helped create. It anchors me in the past, yet continues to create memories for the future. The object becomes timeless.’³

The watch holds significant memories for me, but its also creating something new. The watch is a living motif that exists in the film Baghdad, Iowa and is also a personal object that can be seen and put on display. It is alive and ticking. The mechanics of this watch serve as a simple metaphor as to the whole construction of Baghdad, Iowa. The golden watch is found, and something is triggered in the narrative.

The watch holds significant memories for me, but its also creating something new. The watch is a living motif that exists in the film Baghdad, Iowa and is also a personal object that can be seen and put on display. It is alive and ticking. The mechanics of this watch serve as a simple metaphor as to the whole construction of Baghdad, Iowa. The golden watch is found, and something is triggered in the narrative.

The watch has remained with me until this day. Once when my father came to visit me in Chicago he saw the watch and asked if I needed a new one. I told him I liked it because it used to belong to him. He asked me again if I needed a new watch. “Are you sure?” he would sincerely ask.

The watch never worked until we shot the final scene for the film in the summer of 2014. We used a shower-head and water hose to mimic rain as my character looks at the golden watch. At that very moment my father’s watch began to work and has been working ever since. I consider this a wild and positive omen and a tangible relationship to the fictional film. The outcome affects both the imagined and the real.

Samarra.

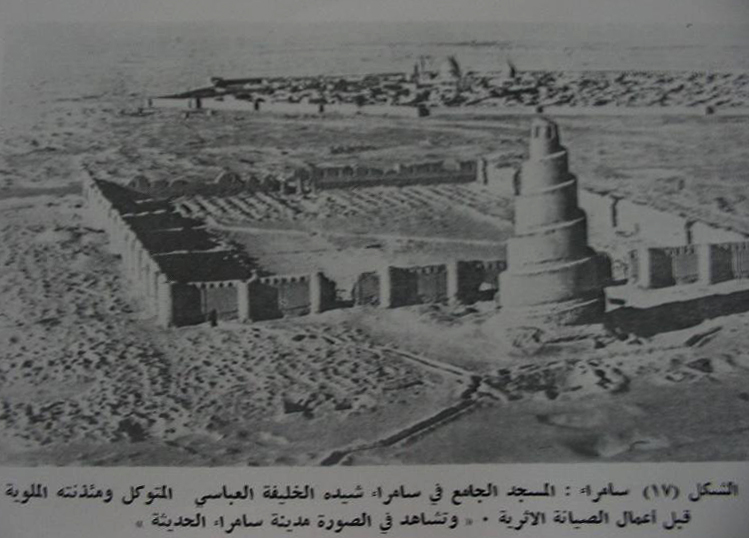

Samarra is an ancient city in Iraq with a famous spiral Mosque; The Minaret of Samarra, also known as the Malwiya Minaret or Malwiya Tower and it’s part of the Great Mosque of Samarra built in the 9th Century. The mosque is one of the largest in the world and in 2007, UNESCO named Samarra one of its World Heritage Sites.4 It is under threat and danger of being destroyed through the conflicts in Iraq.

I’ve walked up that spiral Tower-mosque. I also made a short film called Dream of Samarra that uses my father’s Super 8 film of my ascent upward into the tower. As a child, I used to think it was the Tower of Babel from the ancient Bible tales. I remember looking through an illustrated Bible book and recognizing Samarra in the pictures. “I’ve been up the Tower of Babel,” I would tell my friends.

These are the early sensations of fact and fiction converging in my imagination. I really did climb that spiral tower, and the Tower of Babel in this particular book, is depicted like the Samarra mosque. Many artists’ renditions mimicked the Samarra shape.

How was I to know? Myth exists in Iraq likes facts or gossip about your cousin. It is part of who you are. This symbol, the spiral of Samarra, is desired and emerges in Baghdad, Iowa. The spiral, the shape and its form left an imprint inside of me. It remains there always transforming itself. I kept drawing the tower and eventually it was created in computer animation in the film. I also envisioned it would appear and re-appear.

The Tower of Samarra is a place of conflict and magic. It held my imagination. I was there… I had climbed this tower reaching into the celestial heavens.

This image is an engraving by Gustave Doré, depicting the Tower of Babel in the background, entitled: The Confusion of Tongues (1865).

This image is an engraving by Gustave Doré, depicting the Tower of Babel in the background, entitled: The Confusion of Tongues (1865).

But there was more to Samarra. It resonated on other levels.

There is also a metaphor that originates from an ancient Baghdad story; “having an appointment in Samarra,”5 would signify having an appointment with death herself. In the last shot in the film, as I look out into the landscape, we can see the Tower of Samarra in the horizon. I have accepted that my brother is dead and buried in the earth. I have also looked upon my own fate.

The Forming of the Apparatus.

Baghdad, Iowa, the watch, Samer and Samarra, are the parts that can construct the conceptual apparatus called Baghdad, Iowa. It can use art to help us have relationships with the words and images in a non-technical manner. We don’t really experience life through facts and information. A documentary film has a purpose and can help with understanding part of the world with the apparatus of cinema. But there are emotional memories, dreams, fantasies and objects that need to align for their own type of story. The road takes on that metaphorical meaning of moving towards something better, the eternal song for the immigrant, or the traveler. They are reaching out and away from what is behind. This journey can also be circular. We leave and we long for what we left, and vice versa.

If we take all the emotional connections from growing up in both lands, and the spark of the idea through my brother’s tombstone, we see the formula of Baghdad, Iowa emerge. Its invisible until it is applied to a medium of sorts. If we refer to the apparatus of cinema,6 all of these connections are cross-fertilizing, in a sense, within the apparatus of Baghdad, Iowa.

The creation process is circular. As we create through the apparatus or filter of Baghdad, Iowa, that concept becomes larger and more objects emerge through it.

II. The Apparatus

In the 1970’s there were several film theorists like Jacques Lacan, Christian Metz and Jean-Louis Baudry, who argued that cinema is ideological because of its manner of representation and editing. Jean-Louis Baudry, in his essay “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus,”7 makes the case that all events surrounding cinema are part of this ideological apparatus. Baudry argues that “the specific function fulfilled by the cinema [is] as support and instrument of ideology.” The spectator is crucial to this understanding. The space where they witness the projection of the film, is also a kind of ‘psychic apparatus.’ Baudry says that the “ ideological mechanism at work in the cinema seems thus to be concentrated in the relationship between the camera and the subject.” Thus the role of cinema is to reproduce an idealistic reality. These images and sounds are illusionary sensations that bring the spectator into believing they are the eye that is moving freely. A kind of identification occurs. This effect goes even deeper into the viewer as they sit and allow the images to overtake them.

In the film Baghdad, Iowa, you have several perspectives that support this illusion. One perspective is the camera directly looking out, as a point of view, at times with text as internal thoughts. And other times, the camera is a dream-like companion, it is disembodied and travels freely, hovering over the protagonist’s shoulder – moving us into the unknown. And the third, most typical form or representation, is when we see the protagonist from outside, still maintaining the identification process, like a dream that goes inside and outside of the self.

But the spectator is not passive. They can decide when to identify and when to judge and separate. This is not always a pleasurable experience. It is not always generous. At times we can be inside this conceptual space, and have an emotional connection to the images, and other times, we retreat back into our bodies, into our role as viewer.

Vilém Flusser, elaborates on the technical apparatus: “the Latin word apparatus is derived from the verb apparare meaning ‘to prepare’. Alongside this there exists in Latin the verb praeparare, likewise meaning ‘to prepare’. To illustrate in English the difference between the prefixes ‘ad’ and ‘prae’, one could perhaps translate apparare with ‘pro-pare’, using ‘pro’ in the sense of ‘for’. Accordingly, an ‘apparatus’ would be a thing that lies in wait or in readiness for something, and a ‘preparatus’ would be a thing that waits patiently for something. The photographic apparatus lies in wait for photography; it sharpens its teeth in readiness. This readiness to spring into action on the part of apparatuses, their similarity to wild animals, is something to grasp hold of in the attempt to define the term etymologically. But etymology on its own is not sufficient to define a term. One has to enquire into the ontological status of apparatuses, their level of existence. They are indubitably things that are produced, i.e. things that are pro-duced (brought forward) out of the available natural world.”

In contrast, Baghdad, Iowa, is not a physical apparatus. On the contrary, we are taking the approach of the apparatus and expanding it to the conceptual. The ideology of Baghdad, Iowa is greater than the apparatus, but the production of art and objects (manifestations) are crucial to the concept. It’s circular and keeps expanding, as it gets more specific.

Flusser, if read through this perspective, starts to support these productions or manifestations through our conceptual apparatus in conjunction with the tools, the machines and constructions that make them into being: “tools in the usual sense tear objects from the natural world in order to bring them to the place (produce them) where the human being is. In this process they change the form of these objects: They imprint a new, intentional form onto them. They ‘inform’ them: The object acquires an unnatural, improbable form; it becomes cultural.” 8

The film and other manifestations are clear products of the Baghdad, Iowa apparatus.

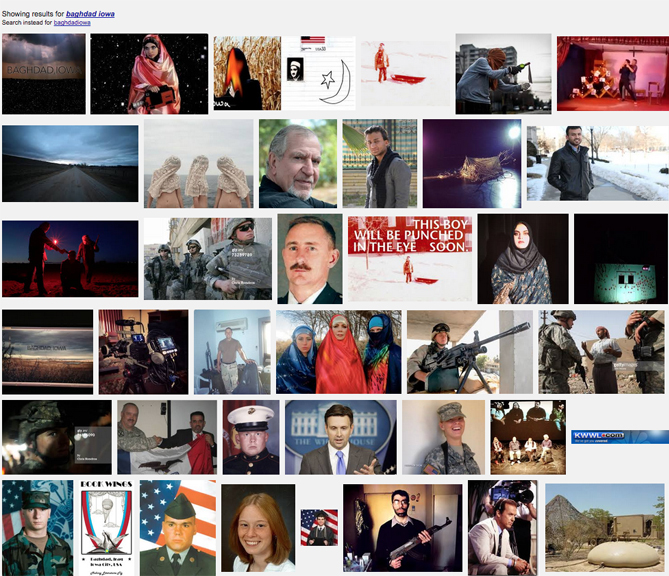

One present version of this is directly connected to the linguistic formula. Baghdad Iowa, as a hashtag or simple search can exist in this form: Baghdad Iowa. The search retrieves the art-work and media sites around this project, but also pulls up all connections between the two words. The search and results are living and current forms of information around a concept.

(Google image search: Baghdad, Iowa, 2015)

(Google image search: Baghdad, Iowa, 2015)

Imagine an invisible three-dimensional egg, floating in space– that is the abstract formula for Baghdad, Iowa. Imagine that egg is continuously hatching out objects, photos, words, poetry, cinema and music. As it does this, it tries to define itself. Baghdad, Iowa is created from that desire, like all manifestations or objects, to make form from formlessness.

This apparatus, with its hatching of materials, becomes the networks for the ‘culture’ of Baghdad, Iowa. Tony Bennett in his essay states: “the case for seeing culture as made up not of a distinctive kind of ‘cultural stuff’ (representations, say) but as a provisional assembly of all kinds of ‘bits and pieces’ that are fashioned into durable networks whose interactions produce culture as specific kinds of public organization of people and things is readily perceptible.”9

In Tim Ingold and Elizabeth Hallan’s chapter, Creative and Cultural Improvisation: An Introduction, they challenge the very notion of fixed cultural practices. They state: “there is no script for social cultural life. People have to work it out as they go along. In a word, they have to improvise.” We can think of Baghdad, Iowa as an organized culture of parts and concepts that like life, is unscripted, or as Ingold and Hallam put it: “cannot be fully codified as the output of any system of rules and representations. This is because life does not pick its way across the surface of a world where everything is fixed and in its proper place, but is a movement through a world that is crescent. To keep on going, it has to be open and responsive to continually changing environmental conditions.”10

This process of improvising, of being open and producing cultural ‘relics’ through the formula or the apparatus that is Baghdad, Iowa, can be applied to many forms as they create. Now that the apparatus is in place, its first output is a fictional narrative through cinema.

III. The Cinema Journey.

Driving is a spectacular form of amnesia. Everything is to be discovered, everything to be obliterated. – Jean Baudrillard, America

There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler only who is foreign. – Robert Louis Stevenson

There are two stories about the making of the film Baghdad, Iowa. The first inception of the film was similar to a documentary – I went on a road trip in 2006, documenting and improvising as I went along, looking for something of the Middle East in the fields of Iowa. What I discovered was that it has always been there.

I kept returning to the photo of my wife Kristie with the white hijab and blue-jeans jacket in Iowa. The footage I shot back then and the unpredictable Polaroid photos of Kristie in the cornfields, migrated into a more fictional construction of the film Baghdad, Iowa, almost 7 years later.

“as soon as we renounce fiction and illusion, we lose reality itself; the moment we subtract fictions from reality, reality itself loses its discursive-logical consistency.”

― Slavoj Žižek, Tarrying with the Negative: Kant, Hegel, and the Critique of Ideology

The second story of the film began in late 2012. I realized I could construct a fictional film in order to express an emotional truth that is lucid and poetic. I was simultaneously collecting information and also creating new information.

“The frame does not simply exhibit reality, but actively participates in a strategy of containment, selectively producing and enforcing what will count as reality. It tries to do this, and its efforts are a powerful wager. Although framing cannot always contain what it seeks to make visible or readable, it remains structured by the aim of instrumentalizing certain versions of reality. This means that the frame is always throwing something away, always keeping something out, always de-realizing and de-legitimating alternative versions of reality, discarded negatives of the official version.”– ‘Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?’ by Judith Butler (2010), Verso, New Left Books

Looking for Baghdad, Iowa.

It was an absurd idea to be traveling to find a place I knew did not even exist. I had been away from Iowa for so long, yet not so far. I was in Chicago after all and Iowa was just across the state line. Iowa was a kind of homeland as well, and I needed to find Baghdad in Iowa. Of course I knew the goal of the road-trip was fictional. But we were still traveling into Iowa and I was determined to find something. So I set out with my wife in the summer of 2007 and rented a car and headed to Iowa.

In my rediscovery I went back to Cedar Rapids to visit the Imam (leader) of our mosque growing up. Imam Taha had left the main mosque in Cedar Rapids and had taken over the Mother Mosque,11 the oldest standing mosque in North America. It was built in the 1930’s. I also discovered El Kader, Iowa, named after a Muslim Algerian revolutionary in northern Iowa. I visited the home of Grant Wood and even shot grainy footage of the famous house that is depicted in American Gothic.12

What I was looking for was not necessarily the town of Baghdad in the fields of Iowa, but rather its shadow – a place I can find internally by looking externally. A friend of mine, an Iowan convert to Islam, was fasting and observing the holy month of Ramadan when I arrived in Iowa City to visit her. She pondered my search for this invisible city. “Perhaps Baghdad, Iowa is the place of two brothers trying to find one another,” she suggested. So we kept driving. I deliberately got lost. The road was the home. The travel, the transition, the eternal leaving and going was a type of life propelled forward. Our car was a moving domestic space. I was submerged in the din of religious radio wrapping me in salvation and damnation. I wanted to bury my own body in the soil. I was anxious for a release from the depression, and mourning that felt so heavy. I missed my brother and I think I was trying to reconstruct him in this trip.

I decided I wanted to expand the more iconic elements of these stories. To elevate certain details that were broad enough – drug addiction, searching for intimacy, the road trip and burial – and move into a narrative. The fictional element became more apparent, though the truth still lurked inside.

Like the land of Oz, it will exist, because the film and objects and art created for it, and by it, exist. It’s a place that can be true if we believe it to be there. Perhaps, I was changing my own personal narrative. I really did need some redemption. Someone asked me if the character I play on screen was really me. I told them it was a more desperate version of myself. I wanted an emotional experience that could be conveyed in the film. I wanted that state of disconnect that happens when a loved one dies. I wanted the body in the trunk literally following our protagonist. I wanted that feeling of being in a liminal state, neither here nor there, neither fully awake nor fully dreaming. I wanted a character that was searching for human connection, closure and love.

The final construction of the film was produced in Boulder, Colorado through the University of Colorado between 2012-2015. The cameras, the crew, and the talent were mostly from the University. I also had my mother involved. She constructed all the head coverings, the hijabs and abayas for the women. And with my direction, she made a niqab that normally only reveals the eyes, but in my version reveals just the mouth. I also worked with other designers who constructed masks with intricate details and precious fabrics, sheer and floral patterns worn on the heads of men with guns, and the vibrant glitter of blue, orange and red for the women, who are also wielding firearms.

The film became a large-scale manifestation of Baghdad, Iowa. Those early digital tapes and photos from the trip to Iowa were barely used in the final film Baghdad, Iowa completed in March, 2015. But that archival media served a purpose. They became a kind of pixilated memory, a psychic blue-print that I could reference.

Motifs, Music and relics.

Within the film, one of the relics of Baghdad, Iowa is a bullet casing from the Iraq and Iran war. These bullets were always around my house in southern Iraq when we lived in Basrah. This large bullet is something that I always held onto. It represents the violent war I went through and the difficulties associated with everything that came after. When I was young, I was very much aware that I could be killed when the bombs started to be dropped and the sirens wailed all night. Being that traumatized had a long-lasting effect on me. I believe it lead to my use of drugs and alcohol as a teen. Just like my brother, I had my own issues with chemical dependency, especially alcohol.

The bullet casing in the film Baghdad, Iowa, makes an appearance with Zada, the mysterious woman who is entangled with my character. She pours me an ancient Arab drink called Arak and uses the bullet to pour water into a small glass as the mixture turns into a milky white. The drink is to help and it also makes things worse. In the film, my character starts dancing wildly with the other hostile patrons at this bar. Arak, literally means sweat in Arabic, the drink takes over and I am truly majnoon, crazed and drunken. The bullet, which is left over from the war of my past, becomes a metaphorical object in the film. The bullet is immersed in the fiction of the narrative film, but also has its own history. It becomes both a fictional and non-fictional object. Like an actor, an object plays a role. This is essential in understanding not only the film, but how the Baghdad, Iowa apparatus can function. Just like the golden watch, which has a similar infusion of fiction and fantasy, they are the components of both the film and concept.

These objects have a story. They belonged to a military tank, or the arm of a father. They have value to me as the person, as their keeper and archivist. But they can also act as vehicles to hold other meanings projected onto them from the audience. A watch and bullet casing are already culturally loaded as objects. They have function and can also be functionless. These objects are symbols and also relics.

Another layer of the project I want to emphasize is the music. The score by Chicago musician Azita Yousefi of Satie’s “Gymnopedie number 3,” to me taps into mystery and wonder. I had her slow it down, changing the tempo slightly of the original and allowing space between the notes. I always felt this deep connection to piano compositions and the forming of Baghdad, Iowa. I couldn’t shake it. Musical scores by Bach and Debussy are also in the film. Again these romantic era piano compositions are part of the construction to help in navigating this emotional road trip. It sets a tone that hopefully will carry you into this visual poetry.

The other music in the film, played by a Middle Eastern experimental-rock band called City of Djinn. That music is the most organic and poignant cinematic component connected to the invented town. I’ve joked with the musicians that they sound like the native folk music that would emerge from Baghdad, Iowa.

The music and the objects collectively are all giving shape and emotional resonance to the conception that is Baghdad, Iowa.

Inanna and Zada.

There are many women in this film. The first one we meet is the sex worker named Inanna. She meets Usama in his motel room. The name Inanna is from ancient Babylon.13 It is the Sumerian goddess of love, war and fertility. There are temples and shrines along the rivers Tigris and Euphrates where it is believed sacred prostitution took place.

Inanna is here, as the name of our professional escort. A sex worker would never use her real name. This name for a sex worker is not so uncommon considering its historical reference. When we meet Inanna she seems educated, experienced and efficient in her task. She wants to help our protagonist. She understands her role is not purely sexual, she is many things to her clients. Our protagonist needs to talk and she can listen. But there is no sacrificial generosity in her. She still needs to get her work done and get out. The night is young and time is money. Inanna is present in this scene to heal and give comfort. Her role has always been sacred. But like many sex workers, she is a merely a surrogate, a symbol of some deeper intimacy or spiritual connection.

The second woman we meet is Zada. Her name is Arabic and means “the fortunate huntress.” Our protagonist is almost child-like in her hands. She wants to bathe him. I’m pulling from my own past here – my memories of being washed by women as a child. My aunt, my grandmother, other women, would kiss me, tease me and I would remain silent and in their captivity. These early sensations play out with Zada. She drinks tea like my grandmother – letting all the sugar sit in her mouth before swigging the entire glass of hot tea. She is teaching me. She is my tutor. Women were always around me as I grew up, and their relationship with me almost disconcertingly intimate. The tension with Zada peaks when she insists on removing her head covering – in terms of Muslim custom, to reveal herself as being as close to me as family. She returns again in the end of the film, as she puts it: I will visit you inside your body. Now shhh go to sleep.

Masks and veils.

This section will spend some time examining the head covering and masks in our current culture, and those that were custom made for Baghdad, Iowa. The veil or the mask, as an idea and object, are an inextricable part of the mechanics of Baghdad, Iowa. The veil in some cases is presented in a straightforward manner, while in other parts it is subverted or transformed into something else – all the while maintaining the concept of a mask, even a non-functioning mask.

The masks have cultural and symbolic meanings. They can reference certain cultural symbols and also act as unique agents in the film.

The hijab, the veil and the mask, all operate on a level of hiding and identifying a person. They can represent an ideology, a faith, or a form of devotion, or even a transgression. It’s a powerful symbol that can be political. These classifications can operate and be linked to a variety of meanings and representations.

Generally speaking, Muslim women around the world wear the hijab or the veil (that covers the hair and much of the head) as a type of religious or cultural obligation or desire. There is no direct quote in the Quran that says women should cover their hair or face. All the Quran says is that men and women must both dress modestly.

Now keep in mind that the hijab is generally accepted almost everywhere in the world. It is only the niqab, or mask that causes consternation. The niqab only shows the eyes, while the hijab only covers the hair.

Do we, as humans feel uneasy when we cannot see a face? What is at the heart of politicizing and regulating how women can dress? When Western governments make laws against the wearing of the niqab, are they sending a hypocritical message? And what about the criticism that comes from the Muslim community of women in niqabs? Many Muslims feel that is going too far with covering the face with this mask.

We need to dismantle some of the misconceptions and also offer alternative perspective. I want to treat each head covering as its own agent– as a concept and garment that can travel through time and culture. If you apply the actor-network theory that Bruno Latour proposes from ‘On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications (1996), we don’t need any human networks when discussing this garment. In this case, the veil within the actor-network theory: “does not limit itself to human individual actors but extend the word actor –or actant- to non-human, non individual entities.”14

As a person who was raised Muslim in Arab-Muslim countries I can speak about my own observed experience from the past and what I see today. My family has home movies from the mid 1970’s of friends and relatives in Baghdad lounging and eating at my Grandfather’s house. Through the scratchy Super 8mm film you can clearly see Arab women belly dancing in jeans or short skirts. The women wore their hair long and wavy, which was the style back then. And if you fast-forward almost ten years, you will see these same women sitting down with hijabs and long dresses. The make-up is still there but they are clearly covered. What happened? Or should we ask, what was decided? Many of these women also immigrated to the United States and went through varying phases of veiling and unveiling.

If we examine the rise of the hijab in the United States, there is clearly no obligation or pressure from society to wear the hijab. You can make an argument that the husband or the father may be hoping for, or perhaps even pressuring the woman to put on the hijab. But this is not typically the case within my community of Muslim friends and family. So when a young Muslim woman, who grew up in the United States and is under no cultural obligation to wear the veil, decides to wear it, we must respect that decision.

In the essay: Redefining Hijab: American Muslim Women’s Standpoints on Veiling, by Rachel Anderson, she states: “For many Americans, the veiled woman symbolizes the oppression of women in Muslim cultures and provides proof that these cultures need to be ‘‘saved’’. In fact, images of covered women have often been used to illustrate the ‘‘backwardness’’ of Muslims and the subordination of women in Muslim societies. However, some Muslim women in the United States also veil, leading many non-Muslim Americans to question their motives for doing so. In fact, since September 11, 2001, Muslim women in the United States who wear face greater scrutiny and suspicion due to a generalized fear of Muslims. To Americans, the veil often represents a tangible marker of difference, in terms of religion and often ethnicity as well.”15

But let’s go back to these so called tensions, and let’s try and dismantle the East versus West argument by looking at young women in Egypt. In the essay entitled The Newly Veiled Woman: Irigaray, Specularity and the Islamic Veil by Anne-Emmanuelle Berger, she talks about teenage girls in Egypt: “who not only wear the hijab but want to wear the niqab (the veil covering their entire face except for the small aperture left for the eyes) at school, against government regulations; the niqab they say, shouldn’t bother or threaten anybody else since it is my niqab: that is, my own business; the niqab thus becomes a means to express or assert a sense of self, as if the more invisible the teenagers’ made themselves, the greater the self-reflecting power of their invisibility: the more identical, the more personal—a founding paradox of identity politics?”16

This paradoxical sense of identity is at the heart of much of identity politics. We can shift meaning. The hijab and even the niqab is benign, a piece of cloth worn around the head. This is exactly why it can constantly shift in meaning and impact.

In the same essay, Berger talks about moving away from this notion that the veil is being imposed on women since many Western countries are seeing more women wearing it. Abderazak Makri, an Algerian member of Hammas describes it as form of: ‘cultural revenge’ against colonialism.

Berger speaks about this, “A number of Muslims are starting to worry about the paradoxical uses and justifications of the hijab by women, arguing that, in present context, the wearing of the hijab has often become a gesture of challenge and display, rather than a sign of modesty and dutiful retreat, thus subverting what they read as the original intention of its prescription. They oppose the hijab in the name of the hijab, as it were, whereas, on the other hand, some well-meaning Western feminist, echoing the “Islamic feminists,’ celebrate the hijab against its grain as a culturally specific and thus appropriate tool in the conquest and assertion of autonomy. Both ‘camps’ seem to agree, however, that such a reading and wearing of the hijab is indeed at odds with the correct one, thus distorting it unexpectedly and threatening the order it is supposed to protect. In a certain sense, this might be true, and one might be starting to witness the effects of this distortion in Islamic countries.”

Clearly the hijab can be worn for religious and cultural reason, but also for political ones and a combination of all of these. The individual decides, in a sense, what it means. Collectively women can alter the meaning.

This paradoxical hijab is played out when the protagonist in Baghdad, Iowa meets Zada and she asks him if he would like to see her hair. The tension is given to her veil and the ‘undressing’ or removing of the hijab becomes a charged gesture. Is it sexual? Is it a gesture of trust? Is it liberating to her? Is it all of these things? Zada fires back and says: I can do whatever I want. The tension is around the hair. The camera gets closer and in slow-motion she removes the veil and ‘frees’ her hair. The moment could suggest an undressing, if the hair is looked upon with any form of desire, or weight. This veil is acting as something that she decides to take off. Why she is wearing it is not clear, but it’s also not within our authority to decide on these things for her. The tension around the veil is not relegated to religious sentiment, but also the imposition of how women should look: to be appealing, to be desirable– for whom though? Catholic nuns are married to God and the hijab holds a similar purist power. We bring our own cultural baggage into this scenario. The hair, in its perceived wildness, needs the contrast of being hidden for this scene to have any impact.

We must be careful, and we must question what our first conclusions are when we see the headscarf or the mask. These factors have always played a role in Baghdad, Iowa. Head coverings and masks have power and are charged with fetish. For the film we have masks with painted faces on them, and one mask has a hole for only the mouth, it ignites the imagination. But most of the time, the head covering are just part of the character’s persona. This is how they dress. What is sacred becomes what is not seen.

The mask speaks to our need to see everything and connect to others in a specific way. For some, the more that is denied, the more tension and fantasy come into play. The mask and veil can play into our desires and fear. It can say much about who we are in the way that we perceive and feel about others.

The unseen is often more revealing than what is seen. We don’t always have reveal in order to know something. The masks and veil is almost its own entity, migrating from screen to object and shifting in meaning.

Cinema of the Unseen.

With cities, it is as with dreams: everything imaginable can be dreamed, but even the most unexpected dream is a rebus that conceals a desire or, its reverse, a fear. Cities, like dreams, are made of desires and fears, even if the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules are absurd, their perspectives deceitful, and everything conceals something else.

–Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

It is important to recognize that when I decided to finish the film Baghdad, Iowa, I decided to shoot it all in Colorado. There is a great tradition in filmmaking to shoot in one place and call it another. It drives some purists crazy, but it was ideal for this project – taking us a step away from factual location, in order to find a clearer fantasy.

The script, at first a documentary of sorts, was now completely a work of fiction and I was using my body, my identity, as the protagonist as a vehicle (in a vehicle) to propel this story. I wasn’t necessarily interested in casting myself, but just like the golden watch,

I could serve a dual purpose. I could still be Usama, but I could also be a fictional Usama.

My past documentary films have established the character Usama, who is sometimes in front of the camera and other times behind the camera. In the film Baghdad, Iowa, the camera hovers next to me. It shifts from a point of view, and then it starts moving further away from me into a wider shot. The camera starts very much like an x-ray into my character’s thoughts. One example, is when we look through the car window, and with the onscreen text, it takes us directly into an internal journey. We are traveling with our protagonist. The camera rarely leaves his side. It is seeing and it is also showing.

The end of the film peels all cinematic artifice, which was to construct forms of narrative and reality, away to reveal humans in agony and in pleasure. The illusion is slow with hands and arms lit up like a chiaroscuro painting – darks and lights, teeth and fingers, all mingling on the screen. We see the natives of Baghdad, Iowa pushing Usama down into darkness on the dance floor. It is simultaneously playful and horrific. The music returns to Satie and the tension is expressed like a feral ballet.

V. Manifestation through the Apparatus.

Since we have outlined how Baghdad, Iowa is a conceptual apparatus that produces specific types of art and media, we can examine these objects and the art manifesting from the concept. These particular arrangements of images, symbols, texts and objects act like codes that are supporting the apparatus and creating it. They are parts that can be recombined, but they all come from the Baghdad, Iowa machine.

The apparatus can be micro and macro. The creation process produces objects, images and sounds that can be arranged in such a manner to signify that it comes from a specific place. That place, bouncing between real and imagined, expounds and becomes a more complex system as more work is produced in its name. In addition to the film, below are various manifestations of Baghdad, Iowa.

#baghdadiowa.

As discussed earlier, the first code uses the words: Baghdad, Iowa. On the most simple level if you type in the hashtag: baghdadiowa, or Baghdad Iowa, you will get a collection of images, words and art connected specifically to the this project, but you will also get other connections to Iowa and Baghdad. These other connections are outside of any control or manipulation. There are the obvious keywords that link us to residents of Iowa from Baghdad, and soldiers from Iowa stationed in Baghdad. But there are surprises: a band’s name by the same title and playing with similar themes; or a writer’s conference in Iowa City bringing in authors from Baghdad. And then there are technical and benign connections, like a link to the time difference between Iowa City and Baghdad. This brings some strange level of comfort to me. This coupling of two words: Baghdad and Iowa, is truly being applied to a massive collection of information and manifestations through the Internet and the technology that generates that information.

Another place to explore is the website: http://baghdadiowa.com which constantly evolving, and will take you to the blog Baghdad, Iowa.

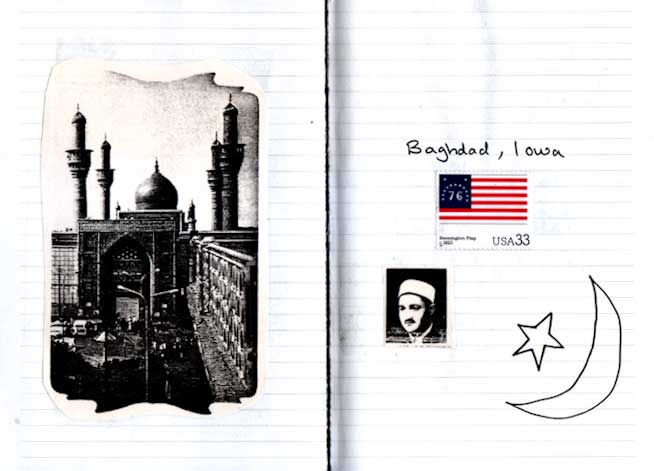

The journal art book.

One of the first manifestations of Baghdad, Iowa was an art and personal journal that I started in July 2006 and has been updated up to the present. The concept was simple back then, I was creating collages and drawings that could visually place all these fractured feelings into one place: a journal as a type of domestic space.

This image has the revolutionary Bennington flag that represented the 13 American colonies that were rebelling against the British. It is the ideal symbol for this sketch. It is the uncertain symbol of a new country. The flag unites and gives a message of independence. The hand drawn star and crescent moon is a generalized symbol of Islam, but the origin is Arab pagan. The face of the man is my great grandfather from Iraq – a man I know very little about. The mosque on the left is Kadhimiya, home to my father and a place that lit up my childhood imagination. Above it all, written by my hand: Baghdad, Iowa.

This simple gesture set the formula in place. The next page, dated July 22, 2006, I speak very honestly about loosing my brother a few months back.

These were the first markings¬– creating the apparatus and being faithful in the creation.

Fatima Johnson.

“I am Fatima Johnson. Born in Baghdad, Iowa. I am Djinna from Kathmia district of Iblis. You know how it goes. Up and down. They say the devil knows my name. But I am neither here or there. What is that word? There is work and there is video signal. They say it’s from outer space. Is this electrical signal our djinna? Stop asking questions. There are dogs and there is one dog and he alone has spent his begotten seed to Son of Fatima, born in history and future. That is my story for now.”

“I am Fatima Johnson. Born in Baghdad, Iowa. I am Djinna from Kathmia district of Iblis. You know how it goes. Up and down. They say the devil knows my name. But I am neither here or there. What is that word? There is work and there is video signal. They say it’s from outer space. Is this electrical signal our djinna? Stop asking questions. There are dogs and there is one dog and he alone has spent his begotten seed to Son of Fatima, born in history and future. That is my story for now.”

Fatima Johnson was one of the first fully formed characters, almost like a Goddess avatar of Baghdad, Iowa. This photo and the colors and art direction was created in collaboration with Seabrooke Mooney, who died in a tragic bus accident in Argentina on February 8th, 2014.

Seabrooke set a color tone in this photo that resonates throughout the whole film. It wasn’t something I had anticipated when I started working with her. The shiny pink and red fabric was like a mythical flame burning into the frame. Even though this particular image is not in the final film, it exists as a photo, as well as stand-alone video, and a manifestation that is a kind of religious symbol. This color palette and tone spreads throughout the film and photos.

VI. Conclusion

“A philosophy of photography is necessary for raising photographic practice to the level of consciousness, and this is again because this practice gives rise to a model of freedom in the post-industrial context in general. A philosophy of photography must reveal the fact that there is no place for human freedom within the area of automated, programmed and programming apparatuses, in order finally to show a way in which it is nevertheless possible to open up a space for freedom. The task of a philosophy of photography is to reflect upon this possibility of freedom- and thus its significance – in a world dominated by apparatuses; to reflect upon the way in which, despite everything, it is possible for human beings to give significance to their lives in face of the chance necessity of death. Such a philosophy is necessary because it is the only form of revolution left open to us.”

Towards A Philosophy of Photography, Vilém Flusser, 1983.

That passage from Flusser reflects the complex networks that have been drawn around the art and film of Baghdad, Iowa. Creating this conceptual apparatus is a way to travel freely as an artist, as a human, so I can create by using almost any medium or form of expression. It can be used to cure madness and navigate through past and present traumas. This ability to move a medium through this poetic apparatus helps maintain this fictional place – and simultaneously networks the relics connected to it. Cinema and art have always done this in some form. Baghdad, Iowa does not even need me. Anyone can be the creator if they make a poetic and proper use of the apparatus.

Baghdad, Iowa is the mask, the shadow and the night stars that sing the sorrow song of death. The traveler is you and the voice you hear is your own. You might be dreaming, so don’t wake up until you arrive in Baghdad, Iowa.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. The Iranian Connection: Before the Mongol Invasion, Encyclopedia Iranica, BAGHDAD i., http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/baghdad-iranian-connection-1-pr-Mongol

2. Searching for the Meaning of Iowa: Word Roots, Prairie Roots (Blog), Cedar Falls Patch, by Ben Prostine, 2012

3. Introduction: The Things That Matter, Evocative Objects, Sherry Turkle, ed. (Cambridge MA: MIT Press. 2007)

4. UNESCO, World Heritage List, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/276

5. Tatanka.com, a version of the story appears in the Babylonian Talmud (תלמוד בבלי), Sukkah 53a.(סוכה): http://www.tatanka.com/topic/parables/appointment_in_samarra.html

6. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus,” Jean-Louis Baudry, in his essay 1970.

7. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus,” Jean-Louis Baudry, in his essay 1970.

8. Towards A Philosophy of Photography, Vilém Flusser trans. Anthony Mathews, London: Reaktion Books, originally published in German in1983, re-issued in 2000.

9. Making Culture, Changing Society: The Perspective of ‘Culture’ Studies, Tony Bennet, 2007

10. Creative and Cultural Improvisation: An Introduction ,Tim Ingold and Elizabeth Hallan’s chapter. 2006, Oxford, New York.

11. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mother_Mosque_of_America

12. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Gothic

13. Inanna Defintion , Ancient History Encyclopedia,, by Joshua J. Mark,

14. ‘On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications,’ Bruno Latour (1996)

15. Redefining Hijab: American Muslim Women’s Standpoints on Veiling, by Rachel Anderson

16. The Newly Veiled Woman: Irigaray, Specularity and the Islamic Veil by Anne-Emmanuelle Berger, 1998, John Hopkins University Press.