Watch my second feature film that I wrote and directed in Chicago from 2003. Watch here.

Category: Blog

We had a great time and my daughter Muneera and partner Kristie were with me.

I was so impressed with the festival and my screening. The screen image and audio were perfect and I loved the tone of the whole fest. It felt important but friendly. I was very honored to be part of this and was very moved by the question and answer session.

Profane is Usama Alshaibi’s third fiction feature film, self-produced with his partner Kristie Alshaibi through their studio Artvamp. It stars Manal Kara and Molly Plunk and was shot entirely in Chicago. The film has won several awards including Best Feature at the Boston Underground Film Festival and Best Experimental Film at the Minneapolis Underground Film Festival. It has screened at many film festival including the Porn Film Festival Berlin, Sydney Underground Film Festival, Lausanne Underground Film Festival and the Chicago Underground Film Festival.

Reflections on Profane written by Usama Alshaibi.

I’ve had this idea for a long time. To make a film about a Muslim sex-worker who is conflicted about her job and religion. The idea of the djinn (a mythological spirit creature made from smokeless fire) came a little later as I was doing my own research. I was born in Iraq and raised as a Muslim. Although in my own family they were not extremely religious or conservative in regard to Islam– we would attend Mosque for special events and we did celebrate Eid. I also lived for a few years in Saudi Arabia where I became much more devout as a young Muslim and started to go to Mosque on a regular basis and reading the Quran daily. But I was also exposed to other things growing up there. I saw pornography for the first time in Saudi Arabia and would hear stories about orgies and drug use. Keep in mind that Saudi Arabia is extremely conservative as the birthplace of Islam– but it also had a lot of wealth. It was a place that had one face on top and beneath it was something else, something more sexual and chemical going on. It didn’t surprise me too much – this hypocrisy and dichotomy between religion and vice seem always intertwined. As I wrote the outline of the character for Muna (the protagonist in Profane) I wanted her to be a real person but to also to embody some of that conflict that Muslims might go through (and for that matter anyone that is devout in their religion).

That was one element of what was driving me to write the screenplay and make the film. The other influence was from a story I heard from my uncle. He told me that he read about a famous Egyptian prostitute who was also a devout Muslim. She prayed the customary five times a day, and after her last nightly prayer, the Isha prayer, she begins to take clients. In the newspaper interview, she says that she doesn’t consider what she was doing as sinful, because she is surviving and feeding her kids. She says she is devoted to God and she knows that God is the only one that can judge her.

I liked that idea that my character would have a very personal relationship with God and form her own private ritual, in her prayers, that is infused with sensual devotion. But I wasn’t sure if I was brave enough to make the film. I was encouraged by my wife. She said “just make it.” So slowly I began, by shooting images of the character Muna. I started interviewing the actor Manal as Muna, who stayed in character. Her narrative and story emerged through that process. I knew that I didn’t want to make a traditional fictional film. I needed other layers of insight into her world. So this style emerged – something interweavng documentary and fiction filmmaking, with an experimental bent to the whole aesthetic.

My own relationship to the Abrahamic faith fueled much of the creation of Profane. In some ways, the film helped me to exorcise my own metaphorical demons. As I grew older I started to identify more as an atheist and was critical of some of the passages in the Quran. But I still consider myself culturally Muslim. I’m still fascinated and entangled in the mythology and rituals of Islam. The Quran is a strange and poetic book. In creating Muna, I wanted her to embody the beauty of the Quran within her prayers and rituals. But she also has a projected fear of what she refers to as her djinn. These supernatural creatures, the djinns, are very much part of Islam and are mentioned in the Quran many times. Unlike the Christian notion of demons, djinns can be either good or evil. Although their reputation is one of mischief. I liked that idea of creating a narrative that obeyed the Quranic rules of the behaviour of the djinn. This mythical, or even mystical, djinn thus becomes something real, or something metaphorical in Muna’s perception of what is happening to her. Is it in her head or is this something real? The implications of this depends really on your own belief system. If you believe in supernatural powers, then she is truly haunted. If you look at it from a scientific perspective, then perhaps she has a drug problem combined with mental illness. I present these issues but I don’t necessarily answer them. That is left up to your interpretation.

There are many practices in Arab culture that come from pagan traditions and pre-date Islam. The evil eye, reading coffee grains, talismans and charms come from old traditions and practices that are usually passed down by generations through women. So from Muna’s perspective, she is in a contemporary way combining her own particular style of praying into core Islamic belief. So she might be in her underwear when she prays, but she does cover up her hair. On the outside that may seem silly, but it’s all a bit silly if you examine it. She is reacting to what she believes she must be doing and what she feels like doing. But she is also using the hijab (head scarf) for a purpose unrelated to modesty. She uses it as a symbol to create a sacred space for herself within her own very personal ritual. So I don’t think Muna really represents Western nor Eastern values. I don’t believe her “Western” lifestyle is that typical of Western attitudes. I think people in the West might be tolerant of prostitution but it’s not mainstream in any capacity. I think it would have the same level of taboo in both cultures. I also don’t think Muna’s excessive drug and alcohol consumption is that acceptable in either culture. But yes, there is a certain diving into vice that Muna explores in the United States that would have to be a bit more secretive if she was in a Muslim country. The irony is that there is nothing she is doing in the United States that she could not do in the Arab world. It’s just more underground in some parts of the Middle East.

There are traditions in many religious beliefs that conflate sensual and mystic/religious ecstasy. Usually, when it comes to religious devotion, we will see passion in reciting of the Quran from men. Rarely will you hear women reciting passages from the Quran in front of Muslims or hear a woman’s voice when it comes to call to prayer. And you will rarely ever see women lead a prayer group. I wanted to preserve Muna’s free-spirit with her belief. She feels very sensual toward the Quran and the prayers, so she makes herself slightly naked to it. She is playing with powerful symbols. In many cultures there is a kind fear and taboo when it comes to women and their bodies and hair. She is placing herself within that energy and making it her own. You also have to keep in mind that what we are seeing is something very private. When she prays in her bra, she is not doing this in public, just alone in her room. As I mentioned before, the headscarf is recontextualized for Muna and becomes a way to remove herself from the mundane and enter into a more meditative or sacred mindset. She places herself as a submissive to God. And in accordance to Islam that is exactly what she should be doing, to submit. So I wanted to reveal that about Muna. That she is a sensual religious person that has her own personal relationship with God. Muna says it in the film when asked why she gave up escorting: I used to submit to men now I only submit to God.

I don’t think Islam as a religion causes any friction within Muna. It’s the people, particularly the men, who want to enforce their own dogma or rules onto her. The religion is benign in a way. It is the men who come to her apartment to ‘save’ her in a way from how she is practicing Islam. They come to set her straight even though she doesn’t believe she is doing anything wrong.

People have asked me if I was worried about making this type of sacrilegious film. I wasn’t too concerned with causing any offense to Muslims. I’m not trying to offend anybody but I can’t control it if they are. I don’t believe the film has caused any offense at any screenings. When I premiered the film at the Chicago Underground Film Festival, there were some Muslims in the audience and they appreciated the film and commented that they knew people like Muna. I think there is way too much fear when it comes to artistic expression associated with Islam. I think because there has been such a back-lash against Muslims in general, it makes it more difficult to make this kind of film. But I think people of Islamic faith will really appreciate my film. But of course you worry about some of the extremists out there. I don’t want to live my life afraid, and we need more Muslims and Arabs to stand up to the religious police and thugs.

The BDSM scenes in my film are very much real. My wife, Kristie, owned a BDSM studio in Chicago called Holy Mountain where some of the women in the film worked. As the name implied, my wife took a sort of mystical or spiritual approach to the business of kink, which made it all the more appropriate to use the space for several of the scenes of Muna in her role as professional Dominatrix. The “slaves” in the film are real submissive men who pay these women for services. I have many friends that are professional sex-workers and I worked closely with them in creating these scenes. Most of them were in the film. I was not so much concerned with pushing boundaries but with showing how Muna and her friends lived and worked. Yes they partied a lot and had a casual relationship with sex. I’m not really trying to test the boundaries; I’m trying to show what I believe to be truthful. Some of the sex and drug-use might be a bit stylized but mostly it draws directly from real life. There is a seedy side to every culture. What I was showing is just this one slice of life.

Much of society shames other humans for how they love, how they fuck and how they pray. I wanted to make a film that was not only a story expressing a unique form of devotion, but also a film that is a testament to the freedom of expression in all its sacred and profane forms.

On March 20, 2003 the United States began it’s “shock and awe” invasion of Iraq. Usama and I had been married for one year and ten days. It suddenly occurred to him that, with the Ba’ath party dismantled, he could return to his birthplace in Baghdad. Now, after receiving political asylum and then U.S. citizenship, he could go back and see his family who had been living there under harsh sanctions and a brutal dictatorship. My husband came out of the shower and said that he heard a voice in his head telling him to go and it would be ok. It was kind of a crazy reason to jump into a war zone, but somehow I trusted that voice too. I told him I wouldn’t let him go alone.

By January 2004, Usama and I found ourselves walking the streets of Baghdad. Our families in the U.S. didn’t want us to go. Usama’s mom was so upset that she temporarily disowned him. And as I breathed in the air thick with kerosine and gasoline, and nervously eyed the tanks and hyper-alert soldiers as they went searching for car bombs just a block away, I wondered just how I got there and why I was being so casual. Journalists wore bullet proof vests. I was in a jean jacket, shopping for DV tapes and mementos to take home.

When I heard the first massive explosion my instincts made me duck and then run for my newly found family in the next room. Usama’s aunt Samaha laughed at me, smiling painfully. She didn’t even budge from her chair. And at that point I realised that this had become the new normal for Iraqis. And that’s when I realised how important it was for us to be there, documenting what was going on for those who had no clue. The stress of it made me terribly ill.

Later Usama and I would be riding in a cab on our way home to our loft in Chicago. The cab driver bonded with Usama over their Arabness, as happened often in that diverse city. Usama introduced me as his wife and the cab driver commented that he couldn’t marry an American girl, because, as he put it, “they can’t take it hard.” Having been to the Middle East I knew what he meant on so many levels. I discovered a lot about my Americanness – about my privilege and lack of understanding – while I was there. The roles expected of women were unnerving to me. I didn’t know that as Usama’s wife there were certain actions I was expected to fulfill, and it led to Usama’s aunt saying that I thought I was “better than” them. Add that to the stress of electricity always going out, perpetually clogged toilets, blockades, curfews, the sound of guns shot in celebration and confrontation, bombs shaking the ground, being barred from certain places for being female, a bunch of socializing and being asked if I was pregnant constantly. No, I could not take it hard. As much as the family tried to make it fun, this was no vacation.

[We chronicled our trip in an on-line blog, found here.]

But what I remember most is the generosity of Usama’s Iraqi family and also how, through it all, they maintained a sense of humor and a sense of hope that things would get better. When I was sick I was attended to by kind doctors within their own homes. Usama’s cousin Tareef and his wife Luma gave up their bed to us for two weeks! We were fed and looked after and shown around like tourists. We were warmly welcomed guests even through the roughest time of our hosts’ lives. And I came away, not really wanting to return to Iraq, but appreciating and loving the Iraqi people, and the culture, so deeply.

So it’s with great pleasure that I’m able to share with you a bit of their lives. It’s my hope that it may solidify your understanding that what we do here – the policies we create, the politicians we elect – have an impact on those other than ourselves. Our country’s violent quest for the Weapons of Mass Destruction was both a wrecking ball, and a moment of hope for Iraqis. Beyond the political upheaval that comes as a result, it is the everyday lives of ordinary people who we tend to forget when when we decide to invade, or “liberate” another place.

Now, on the 13th anniversary of the beginning of the War in Iraq – the war our leaders voted for, and the war we saw plastered on our TV screen daily as some kind of abstract spectacle – we are re-releasing Nice Bombs – My Journey Back to Iraq for streaming rental or download. The voice in Usama’s head was right. We went and we came back fine, if a bit changed by the once-in-a-lifetime experience. And we came back to make an award-winning documentary. But Iraqis are still struggling, and that’s something we need to keep in mind as we watch what was only the beginning of the long road into Iraq.

WATCH THE ENTIRE FILM HERE. Included in your rental or purchase are a number of outtakes from the film, including a visit to a bombed out school where children still attended, as well as interviews with many Iraqi women that had regrettably been cut from the film.

*Nice Bombs is also available as an educational edition for schools and libraries.

–Written by Kristie Alshaibi.

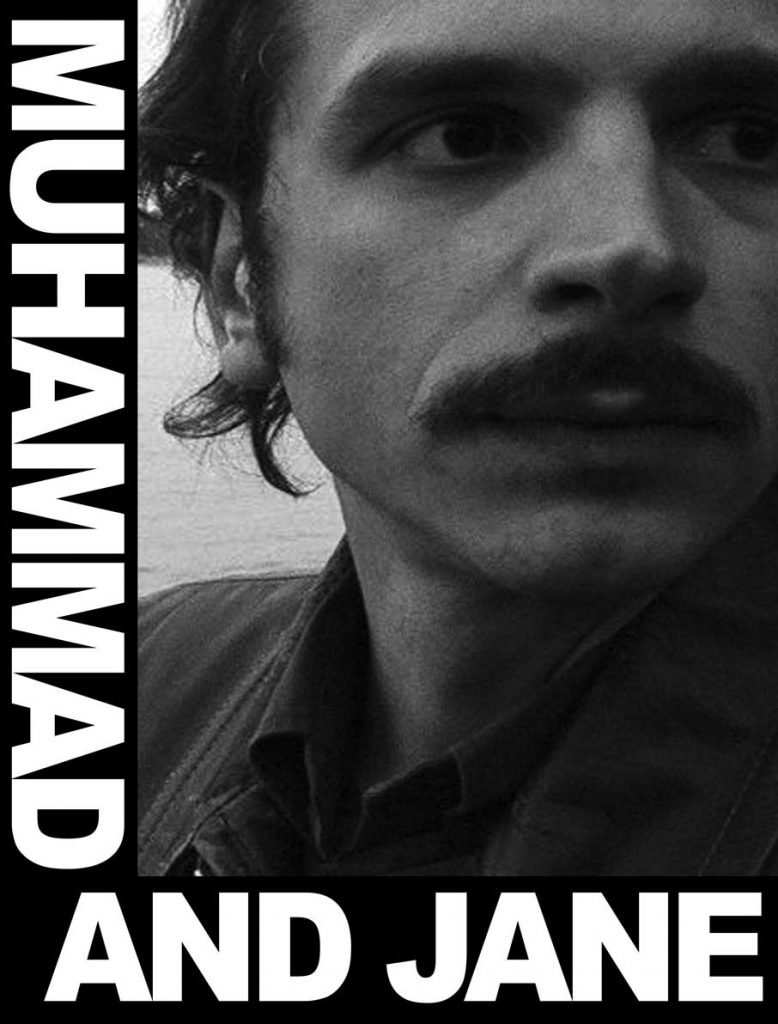

This was made with my daughter Muneera. She wrote it and stars in it. Using black and white reversal super-8mm film.

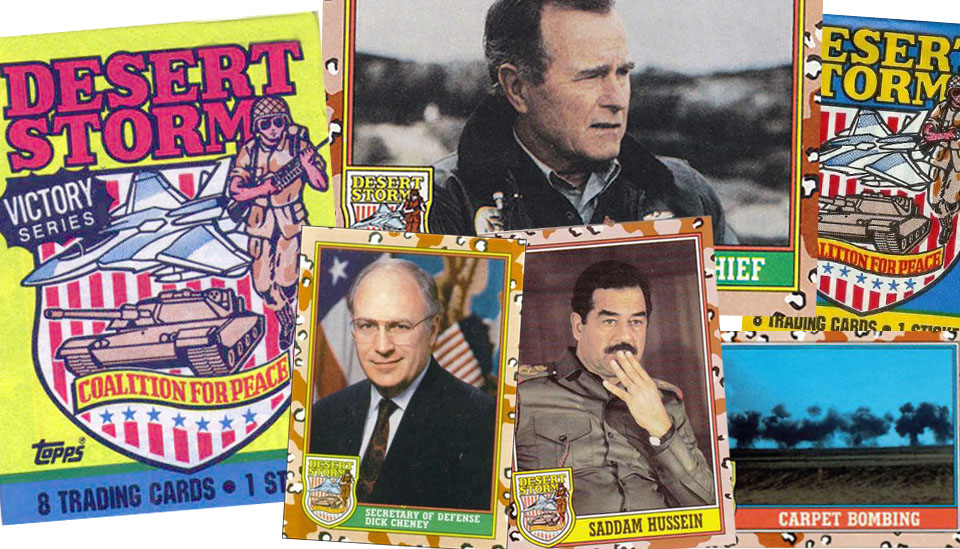

I was 21 years old and living in Iowa City when daddy Bush announced he was going to bomb my home country Iraq. I also lost my legal status to live in the United States and was being deported back to Iraq. And since I was still an Iraqi citizen, I was being drafted into the Iraqi Army. I was going to be deported to serve alongside Iraqi soldiers to fight American soldiers. It was a death sentence. I was afraid. Eventually I went to immigration court and was granted political asylum in order to live in the United States. I had little choice. Dark days. Years before we escaped the Iran and Iraq war, where the United States was supporting Saddam, only to have to deal with another type of horror in America. There was no safety anymore. I remember being in a bar and I met a soldier that had fought in Operation Desert Storm. He said it was justified in killing Iraqi civilians because they were all ‘faggots’. I felt the hatred around me. I lied about where I was from. I also started hearing people referring to Arabs as ‘sand niggers’. It never stopped and just got worse. And here we are again, bombing the Middle East for over 25 years. Millions of Iraqis lost their lives and continue dying for politicians. Clinton with his soft-murder sanctions, just killed Iraqi children in a different way. The American flags went up, the golden ribbons tied around trees, and the blind and bigoted patriotism was starting to shout. What was it all for? Oil and power. And the lies to the poor working class families that they need to send their children to war because of: Freedom, God, Patriotism… it was all bullshit. War for greed and coroporations. We learn nothing. I have never seen peace in my life.

Timely and important. The segment I produced and directed for public television’s Arab American stories featuring the Mother Mosque in Cedar Rapids, the oldest standing mosque in North America.

Promotional tourist video for cinema-art project Baghdad, Iowa.

Welcome to Baghdad, Iowa from Usama Alshaibi on Vimeo.

Baghdad, Iowa is the mask, the shadow and the night stars that sing the sorrow song of death. You might be dreaming, so don’t wake up until you arrive in Baghdad, Iowa.

Stay tuned for upcoming screenings. Watch the trailer.

I’m selling some original art pieces at my Etsy store. Some of these are silkscreens, photos and photo-paintings using light sensitive techniques. Click here to see store.