“What it means to be American needs to be reexamined.”

Two film festivals, two indie filmmakers, one discussion on filmmaking ethics.

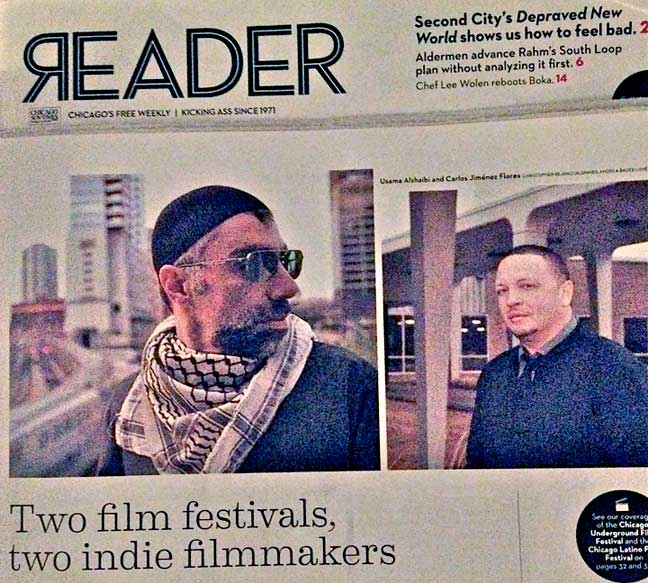

Usama Alshaibi and Carlos Jiménez Flores have different filmmaking styles, but they take a similar stance on mainstream depictions of race and ethnicity in popular media.

It’s officially film festival season in Chicago. As the Gene Siskel Film Center’s long-running European Union Film Festival wraps up, two similarly enduring fests, the Chicago Underground Film Festival and the Chicago Latino Film Festival, are shifting into gear this week. Though they offer wildly different programming—CLFF favors narrative features, CUFF prides itself on experimental fare—both festivals make it a priority to promote small, independent voices. Closing this year’s CUFF is American Arab, a documentary directed by former Chicagoan and Columbia College alum Usama Alshaibi and produced by Chicago’s venerable Kartemquin Films. Incorporating his own experiences as an Iraqi-American with those of Arabs across the country, Alshaibi explores the post-9/11 struggles and contradictions of Arab identities.

For this interview, Alshaibi talked with Carlos Jiménez Flores, a local Puerto Rican filmmaker whose deeply personal feature My Princess, a black-and-white drama shot and produced here, is featured in CLFF’s “Made in Chicago” segment. Like Alshaibi, Flores takes stock of race and ethnic issues, particularly those pertaining to his own community. The two filmmakers didn’t know one another prior to their conversation, but they quickly found common ground in their positions on the ethics of filmmaking and the narrow portrayals of race in media, and their deep connections to their respective backgrounds. —Drew Hunt

USAMA ALSHAIBI: So Carlos, did you study film in Chicago?

CARLOS JIMÉNEZ FLORES: My degree is in human resource development and sociology. I didn’t want to study film. Basically, I’m a storyteller, so I thought human resource development and sociology would give me the depth to tell a better story. I started out as a producer, and always figured I could hire the people who went to film school. Eventually I transitioned to writing and directing.

UA: When I went to Columbia—this was in the mid- to late 90s—there was a real push from the school to work on Hollywood-style film sets. Some of my peers were moving to LA and working on union shoots. I had been to a couple of really massive shoots where there’s a crew of 40 people, but it really turned me off. I just didn’t want to make those kinds of films. When I left Columbia I started to make really small films—just me and a camera and another person. That kind of filmmaking is what I really loved.

CJF: I find it fascinating that you were turned off by being on set with 40 people. That’s how I started, but when I began to shoot my own films I had six to ten people. I’ve been on big-budget sets with big crews, and it’s a little overwhelming.

UA: I totally agree. Even as I started making bigger films, I’ve always kept my crews small.

CJF: The bigger the crew, the less spontaneity you have. With a smaller crew I can say, “Hey, I just thought of something—let’s move this and go somewhere else and shoot a different scene.”

“I started to question whether America was a melting pot. To me it seemed more like a salad, where nothing is blending.”

—Carlos Jiménez Flores to fellow filmmaker Usama Alshaibi

UA: I think what happens in filmmaking is a young person will go on a set, and whatever set they walk onto, that tone becomes what filmmaking is to them. But there are so many different ways of making cinema. When I was starting out everything was celluloid. But I was actually embracing video pretty early on. I really admired the Dogme 95 movement and seeing what was possible with digital video. For one of my early features, Muhammad and Jane, I shot the whole thing on digital video. It was kind of a love story, but it also had to do with the politics of the time around 9/11 and how Arabs were treated and how foreigners were treated. And like your film, My Princessa, I actually shot it in black-and-white because I was interested in contrast. But I remember folks saying, “What kind of film stock did you use?” I’d go, “It’s on video,” and they’d just kind of walk away—which is silly now because so much is shot on video. I think the idea is not to get so consumed with [format] but to remember that the tools we use—film or video or whatever—help tell a story. It doesn’t really matter what you shoot it on.

CJF: Someone can tell an incredible story using an iPhone. I want to ask you some questions about American Arab. I’m Puerto Rican, and Puerto Ricans in the United States are grouped into all these other countries that also speak Spanish. So we’re labeled either Latino or Hispanic. There are debates whether these terms are acceptable or not. So my question is about the word “Arab”—I’m not sure if it’s the proper label over something like “Middle Eastern.”

UA: It’s an acceptable word, but it’s also used to demean. I mean, you can call someone a Jew and say it in a way that’s derogatory. Most Arabs in America would call themselves Arab-Americans, but my film’s title, American Arab, signifies identity. It’s also about process and transition and realizing that the question of identity is very interesting. When I was interviewing Arab- Americans, some of the younger people didn’t identify themselves as white, but some of their parents identified as white. Immigrants who came here in the 50s, 60s, and even the 70s were “white”—unless they were black. If you came from a Middle Eastern country, you were white. Now there’s more of a sense of a brown identity, and people want to be more specific about what they are. I think within ethnicities there are certain complexities, but from a white American perspective people are lumped in these gigantic categories. I’m sure you get lumped. I get lumped constantly. And then we’re cross-lumped. Mexicans or Puerto Ricans are often mistaken for Arabs, and all the hatred and vilification that comes with [the mistaken identity] is attributed to [the target], regardless if they’re from Baghdad or Mexico City. That’s another thing I talk about in the film.

CJF: These themes creep into my work, too, though not directly in [My Princess]. It’s weird because the media in Latin American countries and Puerto Rico, as well, have bought into the views of the United States. They tend to keep lighter-skinned individuals in front of the camera, and I don’t care for that. The reality is we’re all different shades, so in My Princess and in my movies in general, I cast according to talent, not according to looks. I aimed to illustrate all the beautiful skin colors in My Princess, even though it is in black-and-white. I’ve always wanted to make a black-and-white [film] because it’s romantic, a character within itself, but you see the beauty in all the shades.

UA: That’s, in itself, is a type of political statement. And what you say about light skin—it’s not just Puerto Rico. All those skin-lightening products—it’s a huge multimillion-dollar business.

CJF: All of this just reiterates that struggles over identity are universal. The theme of your film connects with me. We need this type of discourse because it will help break down the barriers that have been built over generations.

UA: Absolutely. I think the United States is starting to see the melting pot happen right now. As the landscape of America is changing, this type of conversation becomes more important and relevant. People need to be able to feel like they’re complicated. It’s not like there needs to be any tension between you being an American and you being a Puerto Rican. In another way, you can also say, “I abandon both of these cultures,” and sort of find your own. One of the people I talk to in the film—his name is Marwan Kamel, his mom’s from Poland and his dad’s from Syria, and he said something very beautiful and simple: “Allow people the ability to be complex, give them that space to be complex.” It’s important to allow these stories to be heard, and I think certain filmmakers who have been marginalized in the past also need to be heard. I think what I get from your film is it’s not a simple story, there are a lot of layers and it keeps changing, it’s not fixed.

CJF: I was born in Chicago, but when I was a toddler my family moved back to Puerto Rico. I had no idea I was from Chicago, and didn’t speak any English until I was eight years old. Coming back here, I got an idea of the melting pot idea, [but] I didn’t see it as a melting pot; I was experiencing a lot of prejudice and racism. My father, who was dark-skinned, also dealt with a lot of racism. I saw how he was treated and suffered. When my parents divorced, he went back to Puerto Rico and never came back to the United States. So I started to question whether America was a melting pot. To me it seemed more like a salad, where nothing is blending; it’s just all these ingredients bouncing around this bowl. I agree with you that things are becoming more of a melting pot. I find it amusing that there are people whose families have been here for four, five, six generations—they don’t get that they came from somewhere else. I see how they treat people who just got here like crap, and I wonder what their grandparents or great-grandparents would think.

UA: And it’s not that long ago. For a lot of people, it’s their grandmother or great-grandmother who came here. You and I are the same age. I also was a kid in America in the late 70s, and you’re right, it was tough. Just having black hair was radical. And my father did the same thing as yours: He never quite felt settled here and went back to the Middle East. My mom stayed here, but my father has never really come back. Our stories are common.

CJF: I think films like yours are starting to tackle these problems. We need to break down those walls and start making films that are more inclusive. We need to make films where the bad guys aren’t the same kinds of people each and every time. The media has a huge influence on how people develop these ideas. Most of the things you see onscreen are not real, yet we see it day in and day out, and it becomes the truth. It’s hard to make it in filmmaking, but once you do it’s time to start breaking down the doors—or jump in through the window or come in through the back door. It’s our responsibility as filmmakers to say, “Here’s a different take.” Hopefully we get enough people to come on board and maybe things will start to balance out.

UA: You’re absolutely right. It’s our responsibility to change the visual landscape. The people who are making these Hollywood films have a cartoonish conception of what a Puerto Rican is and what an Arab is. They put the simplest two-dimensional character on the screen, another movie copies it, and they become cookie cutters. We have to beat that down and mock it for what it is. Like, can you imagine if someone did blackface now? They would be laughed at. But at one point that was an acceptable form of entertainment. Hollywood uses brown-face now—Mexicans and Latin Americans are consistently used to play Arabs in Hollywood. Our responsibility is to get in there, talk about this stuff, and change what beauty is—and change what a leading character can be. What it means to be American needs to be reexamined.