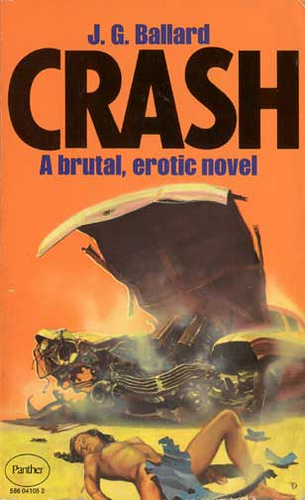

This essay is by writer and film programmer Jack Sargeant. Here he discusses the novel Crash and its relationship to other artist including my films. The novel by J.G Ballard had a huge impact on me when I read it as a teenager.-Usama Alshaibi

Ballard And Trauma by Jack Sargeant

The following notes formed the basis for a talk at the Erotics Conference that took place at Griffith University in Brisbane in February and more recently a public talk as part of the Decadent Society. At some point a more literary version may well be completed for publication, in the meantime, read on.

My interests presented here are crashes, trauma, sex, fetishism, white bandages, bruises, suffering, discomfort and the desire to pay witness to this copulation as chaotic fusion of flesh and technology and eroticized wounds.

Invariably, opening with a quote, used elsewhere to describe both the work of JG Ballard’s Crash and car crash culture in general, but a pertinent point of entry: “She loved accidents: any mention of an animal run over, a man cut to pieces by a train, was bound to make her rush to the spot” – Emile Zola, La Bete Humaine, 1890. Here the swirling chaos of the Industrial Age accident emerges as a moment of spectacular eroticism, a moment in which the spectacle of the sex and death matrix becomes manifest. For the victim: the body losing control over its parts and function, at the mercy of the relentless machinery the coherent logic of the body experienced as coherent self is temporarily erased. In the car crash, thrown forward, wrenched and contorted the body is at the mercy of the vagaries of velocity and gravity, impact and resistance.

Car crashes are a moment in which, to paraphrase Georges Bataille, the profane enters the world of the sacred, where the car becomes a chariot which can deliver the inhabitant to the gods, and for those left behind the marks that remain, the scars of wounds and injuries, retain a hint of the sacred, the moment at which the subject briefly entered the realm of the sacred and subsequently bares its trace.

The scars and wounds of these accidents are, for some, as fascinating as the accidents themselves, a fetish than can be traced back in the case studies described in Psychopathia Sexualis by the pioneering sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing, who detailed the medical fetishists he saw in his consultancy: “Case 94. Fetishism -…Since his seventeenth year he became sexually excited at the sight of physical defects in women, especially lameness and disfigured fee…At times he could not resist the temptation to imitate their gate, which caused vehement orgasm, with lustful ejaculation.…Case 96. Fetishism – …Since his seventh year he had for a playmate a lame girl of the same ago. At the age of twelve…the boy began spontaneously to masturbate. At that period puberty set in, and it lies beyond doubt that the first sexual emotions towards the other sex were coincident with the sight of the lame girl. Forever after only limping women excited him sexually…”

In Ballard’s Crash the author is explicit in his analysis of the wounds from these accidents in his examination of back seat ejaculations, spectacular car crashes and wound fucking. Although fictional there is a parallel between the handful of individuals in Crash and the case studies of Krafft-Ebing.

“Scarred hands explored the worn fabric of the seat, marking in semen a cryptic diagram: some astrological sign or road intersection.” (p.135).

While elsewhere he writes:

[The protagonist] “Watched her thighs shifting against each other, the jut of he breast under the strap of her spinal harness” (p.145)

Later:

“I explored the scars on her thighs and arms, feeling for the wound areas under her left breast… during the next few days my orgasms took place with the scars…in these sexual apertures formed by fragmenting windshield louvers and dashboard dials in a high-speed impact…” (p.148)

Ballard’s novel – famously condemned by one pre-publication reader as the work of somebody who needed professional help – is the Ur text for the transgressive fantasies of car crashes, traumaphilia (arousal from wounds and trauma) and symphorophilia (arousal from staging and witnessing an accident). The book, which follows the author’s namesake who survives a car crash and becomes immersed within a community that fetishises car crashes and the resultant scars and wounds. A book that takes meticulous pains to examine and describe the texture of semen, the moisture of vaginal secretions, the texture of vinyl seats and the musculature of the rectum: “still parting his buttocks, I watched my semen leak from his anus across the fluted ribbing of the vinyl upholstery” (p.166). Anal sex experienced through both homosexual and heterosexual liaisons (as if these simple phrases matter in this world of car crash and wound focused paraphilia, as if gender ever enters the world of the unconscious in which the specificity of the act is what defines the fetish not the gender of the object choice) recurs repeatedly in Ballard’s novel.

This transgressive sexual act, that negates reproduction and so fascinated the Marquis de Sade, finds a link here to the ‘base’ to the annihilation of the self. Sade’s sadism has been described by Gilles Deleuze in Coldness And Cruelty as almost mathematical, with its “repetitiveness” (p.28) and the multiplications of victims and sufferings and in some way Ballard’s attention to detail is similar, but replacing the mathematics with oblique references to technical detail (Ballard and his associates at the literary publication Ambit once organized a stripper – the perfectly named Euphoria Bliss – to performing while a scientific paper was read allowed).

Details matter (from the short film Crash directed by Cokliss): “Her ungainly transit across the passenger seat through the nearside door. The overlay of her knees with the metal door flank. The conjunction of the aluminized gutter trim with the volumes of her thighs. The crushing of her left breast by the doorframe, and its self-extension as she continued to rise. The movement of her left hand across the chromium trim of the right headlamp assembly. Her movements distorted in the projecting carapace of the bonnet. The jut and rake of her pubis as she sits in the driver’s seat. The soft pressure of her thighs against the rim of the steering wheel.”

They contribute to the apparent authenticity of the fantasies articulated here. Mere action is not enough, details matter, from Vaughan’s Lincoln to the description of the flickering lights of indicators of police vehicles illuminating the twin copulations associated with human coitus and the metallic penetrations of accidents.

The nihilism of Crash is overwhelming, the protagonists negation of nature and even the self, again echoes Sade, the desires are so all consuming, they consume other and self, until all that is left is ruined metal, Vaughan’s desires are to kill his target and himself simultaneously. As a protagonist Vaughan recalls Sade’s sovereign man – that figure who exists beyond the sadist / masochist dyad, an affirmation of lived experience – in Vaughan manifest as sovereign man pursuing his own desires up to and including his own annihilation, experiencing every pleasure (up to an including the pleasure of annihilation).

The roots of the story of Crash can be found in Ballard’s previous book, the experimental novel The Atrocity Exhibition and in an April 1970 show curated by Ballard at the New Arts Lab in London. Crashed Cars featured three car crash ruined cars, dragged from wrecking yards and exhibited in the gallery. The opening night of the exhibition was marked by the presence of a topless model (although she was meant to be nude when she saw the ruined cars she refused) asking questions of the audience. According to Ballard’s autobiography Miracles of Life (p.240) over the following month viewers responded with outrage, with people attacking the cars and even, bizarrely, Hari Krishna’s throwing white paint on the cars. If Vaughan’s sperm scribblings described previously are some primitive sigils then this seems to be a form of ritual cleansing, as if both driving out and calling in the forces of autopic chaos.

Little known, and barely mentioned beyond Ballard fan circles, is the short film Crash directed by Harley Cokliss (aka Cokeliss – a director known for b-movies and tv shows [as either if these was bad]), this short film made for the BBC who broadcast it on BBC2 at 8:30pm two days before Valentines Day in 1971, can be found on Youtube, starring Ballard and actress Gabreille Drake (then famous for appearing in the television series UFO) it follows as Ballard – also seen onscreen – expands on the general themes that would subsequently inform Crash, while Drake enacts the role of driver and, of course, invariably, sexy car crash casualty. Thanks to – presumably the BBC Radiophonics workshop – the short film is scored by pre-industrial music / avant-garde noise, while Ballard – in beige suit – describes the human relationship to the car, the highway, while noting in fetishistic detail the movements of women climbing out of cars. Juxtaposing forms of car with curves of women’s bodies, creating a montage of eroticism. The second part of the film is dedicated to the car crash, with the author walking around ruined cars describing the fictions of the everyday manifested through consumption and car crashes, “if we really feared the car crash” he says “none of us would be able to drive a car.” In the wrecking yard Ballard glimpses women. Before discussing the style of the instrument panel as the model of our wounds. Footage shows Drake – moments before seen in the shower, her flesh, her curves and her nipple dripping with fresh water – now blood soaked and slumped over her steering wheel, the soundtrack a synthesized alarm escalating in intensity.

Ballard’s glorious fusion of sex, injury and death in the car crash realized in this short film plays on images of blood and sex, the thick heavy blood pooling on her skirt indicative of abdominal injuries, perhaps even genital injuries, her breast “bruised”. Realized with greater clarity in the subsequent Crash where the author speculates on such injuries before, later, describing a back seat fuck resulting in “bruised vulva”.

I do not want to examine David Cronenberg’s 1996 film here today. A thorough interpretation of the source material, it dances through the themes with vigor, although its cold tones never fully embraces the inherent fetishism of the traumatic, however the sight of Gabrille’s (Rosanna Arquette) legs gripped in braces as she rubs herself against a car, her short skirt rising high, is powerful, it is undone by the crass climax of the scene which sees her leg braces tearing the leather upholstery. Such images stop the film from being as unsettling – perhaps even uncanny if Ballard’s psychological description is correct – as it should be.

Instead I wish to move on to examine the emergence of traumaphilia as a source for others working in the post-Ballardian universe. Traumaphilia – the paraphilia in which the subject is aroused by wounds (sometimes referred to as traumatophilia) – can be seen in the medical art of French photographer, occasional filmmaker and fine artist Romain Slocombe whose fetishistic artistic practice depicted Asian women wrapped in crisp clean white bandages (and, to a lesser extent, in the popularity of the nurses uniforms and bandages that can be seen at some fetish clubs worn as fetish wear, although the nurses uniform is not primarily related to trauma, when played alongside bandages and the accoutrements of the emergency room, there is an element of traumatic fascination at play).

While the traumaphile is not necessarily interested in how the injured object choice came to be hurt, Crash and the car crash serve as a common source of injury and the interest in the injury. In his book Tristes Vaccacion (Sad Vacation), Slocombe’s paintings of bruised and bandaged girls are punctuated with descriptions, which detail the injuries and their sources, positioning the text / artwork within the same realm as the Sadean lists. Slocombe’s work continued to explore these themes in the collection Japan In Bandage includes images such as L’Ar Medical (1982), which depicts a naked patient in a hospital bed, bandages and orthopedic devices holding her – like bondage – in place. In the background there is an image of a car, similarly Bonne Route (1992) depicts a heavily bandaged woman standing next to a poster of a car.

The violence, as Slocombe has stated, in his work is located in the past. He is not necessarily interested in the moment of violence, the single act but the process of recovery. Car crashes, with their speed and rapid climax, are violent moments that are almost instantaneous, like film a rapid cut, a gap in time, then impact. The pleasures of watching the process of recovery – or recovering in a hospital bed – can neither be fully sadistic or masochistic, traumaphilia appears to operate in both yet neither zone, concerned as it is with everything from the mise-en-scene of the hospital and patient (white bandages, clean tiles, sheets) through to suffering (the patient restrained by surgical devices) through pain (the bruises heeling yet simultaneously so sore), and so on.

If Slocombe visualized the trauma, then American underground filmmaker Usama Alshaibi has taken it to the next level. Working in Chicago since the 1990s, Alshaibi has directed a string of short films, each lasting only a matter of minutes and exploring aspects of sexuality and fetishism (he has also made features and documentaries, but these are often very different to his shorts). In Convulsion Explosion a woman painted white and wrapped in bandages squirts red paint / stage blood from her rectum, the play here is not necessarily on the recreation of trauma so much as on the play of colours, the red and white, the texture of bandages and painted skin. In Traumata the camera plays over a naked young woman’s body the bruises, bandages and leg cast indicative of unspecified injury, while he dour expression indicates her humiliated discomfort. As if the audience and camera were intruding on her pain. In Gash the camera is turned onto an open wound a few centimeters from a woman’s vagina. The erotic potentialities of penetration doubled. In Patient a not quite naked woman writhes on a bed, her head wrapped in a bandage. These films play with trauma and traumaphilia, recognizing the fetishistic gaze onto the ‘wounded’ female, whose suffering – already in the past – is nevertheless born out on the marks that criss-cross the soft flesh.

No explanation is proffered in the films, short vignette in which the gaze on the injuries and suffering flesh appears as both first cause and intent.

There is a violence here that has happened, death has been momentarily thwarted, but the marks on the flesh remind the viewer (and the subject) of the transient nature of existence. But there is more at play here, more at stake, in paying witness to the accident and recuperation there is a sense of power of life over death. The ruined but healing body emerging as a locus of visual pleasure. To quote Paul Morrissey’s Flesh For Frankenstein, “to know life… you have to fuck death in the gallbladder”.

Reprinted with permission. Source: Ballard And Trauma by Jack Sargeant.