“In that uncertain moment”: Talking Nice Bombs with filmmaker Usama Alshaibi

By Ray Pride

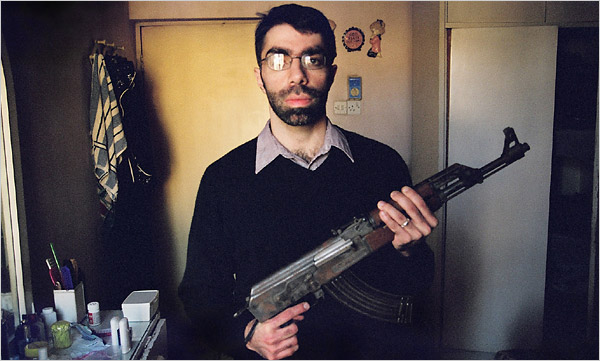

NICE BOMBS IS CHICAGO FILMMAKER USAMA ALSHAIBI’S FORCEFUL DIARY-STYLE DOCUMENTARY about the first visit he and his father and his American wife made a journey back to their native Iraq after the American occupation had begun. The last footage was shot for the film in 2004, when the conditions in Baghdad and Iraq at large were not as dangerous. The Siskel Film Center’s Barbara Scharres writes, “After an absence of 24 years, Chicago-based director Alshaibi, now a U.S. citizen, returns to his native Iraq with his father and his wife to make a film. American-occupied Baghdad is in part a time warp (his childhood slide is still in the yard), but the daily fear of bombs and random gunfire casts a chill over the family reunion. This remarkable inside story movingly explicates the confusion, anger, and stoicism of ordinary Iraqi citizens caught in a living hell as hope for freedom from fear rapidly wanes.” While the movie begins in a straightforward fashion, it gradually turns toward the more impressionistic style of his earlier work, culminating in a phone conversation set against a brilliant Chicago sunset with subtitles scattering around the frame. One particularly striking scene, showing a lack of sentimentality involving a dying cat, makes sophisticated critique of misplaced audience empathies. Alshaibi has been a prolific maker of shorts and videos on the Chicago scene, and has made experimental features as well, such as 2002’s Soak. Nice Bombs won a best documentary prize after opening the 2006 Chicago Underground Film Festival.

PRIDE: I’ve seen a couple of cuts. Did you make a TV cut and a theatrical version?

ALSHAIBI: There is only one version and that is 76 minutes. It was originally 92 minutes, the one we showed at CUFF last year, but after sitting on it for a while and not being happy with the cut, I decided along with the Benz and my new distributor Seventh Art Releasing to cut it down. The stuff I cut out was in the beginning. The interview with my sister, my Mom, all that is gone, and instead-it cuts straight to the journey into Iraq. I think the style of the doc pops out even more with this shorter edit. You talked about that style toward the end of the film—

PRIDE: Yeah. The film, to me, has two distinct parts, as I’ve said before–the chronology and family recollection and reunion that is more traditionally done, and then the later parts which drift into the more stylized, experimental wont of your earlier work. Is that still pretty much the case with this one? Were the two styles at war with each other during editing? If my memory’s clear, you said you discovered the later part, especially the phone call with the Chicago sunset and floating supertitles, toward the end of finishing the film.

ALSHAIBI: Well, that framing and showing stills and cropped movies does connect better on an aesthetic level now with slow talking heads cut out. The backstory leads us into Iraq and we spend the majority of the film there. I cut out other interviews that were too long and did not work.

PRIDE: Is all the stuff with the dying cat still there? Do people react to that in an instinctive way or do they take something more from its inclusion?

ALSHAIBI: The stuff with the cat is all there. People react differently to it. I keep hearing about the cat. Even after a year I have some people asking me about the cat.

PRIDE. What’s the most surprising reaction you’ve gotten from an audience at large or an audience member?

ALSHAIBI: The most surprising reaction? I don’t know if it was any specific reaction but I am always interested when people react in this very emotional way to the film and draw their own conclusions about the war, Iraq and my family. I think the most surprising is that people ask me about my cousin Tareef and my Dad and seem genuinely concerned and affected. That has been a touching experience.

PRIDE: Can you talk about Studs Terkel’s connection? He was frail but bold at 94 when he introduced it at CUFF last year.

ALSHAIBI: Studs and I are buddies, in a way. I worked under a grant to archive his audio recordings for many years at the Chicago History Museum. He interviewed me for [one of his books] and I told him about my desire to return to Iraq and make this film. He pushed me to do it and bigbombposter.jpggave me some cash. So I had to go! He signed on as executive producer to help with exposure. Christie Hefner and Studs are friends and so it was a nice way to get Playboy Foundation and Studs together to present the film. Playboy Foundation gave Nice Bombs a grant.

PRIDE: This film seems to be your leap from out of the so-called “underground,” but CUFF was good to you in 2006—

ALSHAIBI: CUFF was good to me in 2006 and Playboy, Benzfilm and the Music Box all helped with that premiere. I will probably always be playing my shorts at various underground or experimental film fests but I do want to make work like Nice Bombs that is accessible to everyone and anyone. This has become important to me.

PRIDE: Do the interviews you edited out make the film less personal to you? More political? More streamlined, is what you seem to suggest.

ALSHAIBI: No, not less personal, even more so. It keeps the narration going without so many interruptions. More streamlined and I was also able to tweak some parts to make the scenes more clear. It is definitely a more coherent documentary that is closer to the soul of the experience.

PRIDE: So finally it’s locked, loaded and out there: I’m sure there’s something to be gained from the stock question of, what have you learned?

ALSHAIBI: To trust my instincts but to also balance that with patience and observation. I’ve learned to listen.

PRIDE: How do you see it fitting into the context of the uncertain moment we’re all in?

ALSHAIBI: I think it stays there, in that uncertain moment, hanging out to make sure Iraq is not ignored for the sake of American impatience.

PRIDE: How long ago was the last visit to Iraq in the film?

ALSHAIBI: February 2004.

PRIDE: Is there news of your relatives?

ALSHAIBI: My uncle Kamil, the older academic, died from old age. My cousin Tareef has fled to Malaysia to protect his family and to complete his Ph. D. Malaysia is one the few countries that accept Iraqis. Some have fled to Syria. The American couple had to leave and are now in Europe. The Swedish-Iraqi woman and her husband moved to UAE. Many people had to leave. My other uncle Abdullah had to sell my grandfather’s house and moved to Jordan. I’m losing all my relatives over there. But there are still many Iraqis that do not wish to leave. In fact, my Dad has been going back to Iraq for some work.

PRIDE: You’re also developing more things with your audio experience?

ALSHAIBI: Oh yeah, I work now as a host and producer for a new radio/web station called Vocalo. It’s the product of Chicago Public Radio but we don’t sound anything like public radio. We have music, audio pieces and listener-created content. It’s still in the early phases, but I left the [Chicago History] Museum to go work there full-time. I like it. It’s a creative job and I work with some really talented people. It keeps me excited. I’m still creating these mini-docs, but within the realm of audio. It’s helping me get better at creating short audio modules on all sorts of subjects. They can be simple or complex and I keep moving and discovering people and the city. It keeps me fresh and gets me out on the streets.

http://www.mcnblogs.com/mcindie/archives/2007/07/dropping_nice_b.html

This interview is © Ray Pride (July 11, 2007), no parts of it can be reproduced without the author’s written permission.