Film Bizarro Interview: From Real to Surreal with Usama Alshaibi (February 2010 )

First of all, thanks for agreeing on doing the interview. Could you introduce yourself?

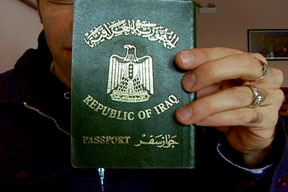

My name is Usama Alshaibi, Iraqi born, United States citizen. Filmmaker, artist…

How and when did your interest in film start?

Well I had always been interested in art. Especially as a child. I drew all the time. I would try and copy some of the great masters… I studied art and painting briefly in college. I had always played with video and would mess around with my Dad’s super 8mm film camera. So I knew film and video early on. But it was not something I got into until later… I started playing more with Super 8mm and started working in photography. 35mm, processing black and white. When I started watching films by Wim Wenders, Roman Polanski, and all the Cinema of Transgression stuff that I thought… hmm I’d like to do this. So I went to film school in Chicago. But still I was trying to find my voice. The school I went to really trained us to be more like Hollywood directors and I was not really interested in that model. I was interested in playing in places like the New York Underground Film Festival and the Chicago Underground Film Festival…

That’s something that I’ve really found interesting about you.. Cinema of Transgression is a very specific subgenre, and it feels like very few filmmakers nowadays “get it”, or even know of it. What was your first attempt at making these films?

I was aware of experimental films and such. But the Cinema of Transgression just seemed to speak to me directly. They were playing the music I listened to and the people in the films looked like some of the folks I hung out with. There was something seedy and perverse about it. I guess that first film that I made that was not a nod to that movement but me finding my own voice was called “Dance Habibi Dance” it played at New York Underground and played all over the world. It was my first taste. Shot on 16mm film and was totally unlike anything I was trained to do. It was also playing with my own cultural roots. So it was not just copying something. There was nothing like it.

You have alot of your films online for streaming, is this something you see as a possibility to get your name out?

Exactly. But back in 1998 up to 2001 it was still a new idea having your films up online. This is before Youtube and Vimeo and I already had my short films up online in these various sites. It was still a new idea and I remember many filmmaker being horrified that I was just “giving away” my work. I never saw it that way.

I agree with you in many ways, that it’s not about giving it away, but rather a new way to get it out. Of course, selling a DVD is a good way to do it still, and I always prefer buying one over streaming. But at the end of the day, alot of people don’t want to pay for something they know shit about.

In the old days a director would make a music video and hope it gets played on MTV. Now we show it off on Youtube. Early on, I was very much aware that the new theater, the new way of looking at films was going to be on tiny monitor and computer screens, phones, etc. So I thought more of one person privately watching my short films instead of a whole audience. Although I still show at many film festivals. But the experience of watching something online is totally different than having to find it somewhere. Although there are many of my films that I can’t really show online due to censorship. So we still have to have other means, like DVD. I kind of do both. Like I would not want to give away “Nice Bombs”. And there are many of my pieces that you can only watch on DVD. The dialogue I have with some of the online films is fascinating to me. Like “Allahu Akbar” just read all the crazy ass comments on youtube. It brings a new perspective that I did not intend:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FqKU_1pGndw

I have seen alot of your experimental videos, but have yet to see “Nice Bombs”. What can you tell us about that one?

The USA invaded Iraq in 2003. I thought it would be a good time to go back to Iraq. I was born there and had escaped with my family as a child and had been away for over 20 years. With my wife and my Dad we returned to the most dangerous city in the world in early 2004. I made a movie about Baghdad in time of war with a mixture of my own story. That movie had changed my life.

That must have been both hard and interesting for you to make?

Yeah. It was a tough time. When I got back to the USA my younger brother died from a drug overdose. The war in Iraq was getting darker and more violent. It was a rough time for me. I had some media attention over the film and it did pretty good. But emotionally it was a challenging and very personal film. I’m happy I did it though. It took a lot out of me but I’m okay now.

I find it very interesting when documentary filmmakers set out to make a film in the most terrible places to be, and same goes to the News people who run around in the middle of battle. You must’ve grown as a person from doing something like that, and really made you appreciate life in a new way?

Yes. But unlike a news person that goes to a foreign land to cover some catastrophic event, I was from Iraq. I already had a history and I was going back. I was returning to something that I feared. War, death, being kidnapped, or even worse having my blond haired American wife kidnapped. It was dangerous. We literally had to drive from Jordan to Baghdad. No airports. No bullet-proof jacket or security. It was just me and my camera. It did change me. It changed me forever… and it also set me into a new course in filmmaking. I was able to go deeper into this film and explore many aspects of life in Iraq and my relationship to it… I guess what I’m trying to say that the experience of the documentary went far beyond the film itself. So the movie elevated my work to a whole new audience. Getting a broadcast premiere and theatrical release was a totally new experience for me. So “Nice Bombs” not only changed me as a person but as a filmmaker as well.

You mentioned your new film “Profane” earlier, that it was a morphing of your different films. In what way do you think “Nice Bombs” influenced the making of it? If it did, of course.

My brother was a devout Muslim but also a drug addict. So I was interested in this duality a little. I was raised as a Muslim and was very religious myself when I was a teen living in Saudi Arabia. But after I left Islam I started to look back into who I was, what Islam was and what my culture or traditions meant. It started slowly with an ongoing experimental project called “Baghdad, Iowa” (http://baghdadiowa.com) and then lead to “Profane.” The connection to ‘Nice Bombs’ is probably being more comfortable and aware of the complexities of Islam and Arab culture. I wanted to use Islam as a theme in the horror genre in the same way that Christians use these images and beliefs. The notion of Jinn’s and Satan (or Shaytan in Arabic) is a very powerful element in Islam. There are many minority cultures in Iraq and religious beliefs that even pre-date Islam. Remember the beginning of the “The Exorcist” takes place in Iraq.

What more can you tell us about it? There is a sneak peak of it at ProfaneTheMovie.com, and personally I thought it almost makes it seem like a movie about possession.

It is a movie about possession. According to Islam mythology we each have our own Jinn. God, or Allah created humans from clay, angels from light and jinn’s from smokeless fire. But in my movie it is an inverted exorcism. In Catholic ideas of demon possession you try and get it out f the person. In my movie, my main character has lost her Jinn and is trying to get it back into her, in order to not be possessed.

It is a movie about possession. According to Islam mythology we each have our own Jinn. God, or Allah created humans from clay, angels from light and jinn’s from smokeless fire. But in my movie it is an inverted exorcism. In Catholic ideas of demon possession you try and get it out f the person. In my movie, my main character has lost her Jinn and is trying to get it back into her, in order to not be possessed.

You also mentioned that you injected these subjects into the horror genre, so would it be correct to call this a horror movie in the traditional sense?

You can call “Profane” a horror movie. In the traditional sense… maybe. I have not seen Islam used in this way. It plays with certain expectations and I am also trying to show you something. There are many levels to the movie. For example, the main character, Muna, she is a pro-Domme. That is, men submit to her and pay her to beat and humiliate them. And she, in her way, is submitting to Allah. The very meaning of “Muslim” means to submit. Even in my “fictional” films there is something that tries and reveal a truth. Not just documentary for documentary’s sake. But something that is truthful about this person. That comes from real life. So I may set up artifice of horror and Jinns, but I am trying to show something truthful about Muna and her life. I have never been comfortable with just making something totally non-fiction. I am always taking something from reality, always. I wrote, directed and shot it and now I am editing it. I am working with a very talented Iranian-American musician named Ehsan Ghoreishi. This style of doing everything myself is how I used to make all my work…but I don’t do that with all my work now.

I guess filmmakers often come to a point where they need and want a bigger crew. I dont mean like a Hollywood film where they want hundreds to do their hair, but I think its important for filmmakers to expand through working with others.

Yes and my most recent new doc, in production, I am working with a full production company and crew. I crave that now. I want to hire an editor and cinematographer. I get burned out doing it myself! Plus it feels so much better to just write and direct.

We need to round this up now, so I want to thank you for doing this interview with us, and I look forward to seeing your future work. Do you have anything to say to our readers?

Thank you! I want to say that we need to support more independent filmmakers that truly operate outside of the conventional mainstream cinema world. We need more diverse, and unique voices in film, to offset the corporations that are turning our media into a mono-culture.

Cheers! And take care.

Take care buddy!