From Iraq to Iowa

With a little help from Kartemquin Films, Usama Alshaibi documents the Arab-American experience.

By Ed M. Koziarski, Chicago Reader, August 5, 2010

“If you think you know what an Arab is, you don’t,” filmmaker Usama Alshaibi says. “I don’t know either.”

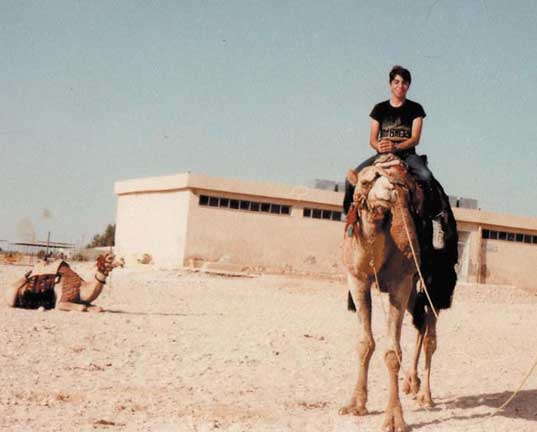

Alshaibi is an Arab himself, born into a moderately Muslim household in Baghdad in 1969. For a time he was very religious, but now he’s not at all. He grew up in Iraq and Saudi Arabia and Jordan and Abu Dhabi, but also in Iowa City. He was a young man knocking around America when he got word on the eve of the Gulf war that the Iraqi government wanted him home to join the army and help repel the American invasion.

In early 2004 Alshaibi did go home, and documented his first trip to Iraq in 25 years in the film Nice Bombs, his most successful project to date—it got a limited theatrical release in 2007 and aired on the Sundance Channel in 2008. For the documentary he’s working on now, called “American Arab,” Alshaibi decided to sort out his experience, and the experience of others like him, on this side of the world. “It’s been pretty emotional to dig deep into this stuff and remember what I went through and to be honest with myself about how I really felt growing up here,” he says. “There were moments I was really embarrassed to be Arab. It took me a while to be cool with that.” As part of a benefit to raise funds for the film, he’ll screen a 14-minute excerpt this Thursday, August 5, at Stan Mansion in Logan Square.

Alshaibi went to kindergarten in Iowa City while his father, on a scholarship from the Iraqi government, studied for an MBA at the University of Iowa. “I didn’t really know what Islam was,” he says. “We celebrated Christmas. My parents sent my sisters and I to bible camp during the summer, to get rid of us.”

Yet he felt far from assimilated. “When I was a kid I felt like no one was like me here in the U.S. or in the Middle East,” Alshaibi says. “It’s this strange cross-cultural identity that’s almost a third identity. It’s neither/or.”

The Alshaibis returned to Iraq when he was in fourth grade. They moved to Basra, because Alshaibi’s father couldn’t teach business in Baghdad without joining the ruling Ba’ath Party. “Going from an American-style public school system to Iraq was a big shock,” Alshaibi says. “My grandfather asked me if I was reading the Koran in America. I said, ‘Yeah, grandfather, but we call it the Bible.'”

In 1980 Iraq invaded Iran in an attempt to occupy the oil-producing and largely Arab province of Khuzestan. This set off the eight-year Iran-Iraq War. “My dad would say, ‘We’re on the good side, the U.S. is supporting us,'” Alshaibi says.

Near the Khuzestan border, Basra suffered nightly bombing raids. “It’s a strange feeling as a kid, to realize your parents can’t protect you from war,” Alshaibi says. “I was grabbing for a higher power.” He grew increasingly religious—even more so after he and his family fled the war in 1981 for Saudi Arabia. (Their house in Basra was bombed within months of their departure.)

Alshaibi’s two sisters were born in Iraq, his two brothers in Iowa. The family lived wherever his father found teaching jobs—in Saudi Arabia for two years, then Jordan, then Abu Dhabi. He was in ninth grade when his mother, who wanted to study fashion design, took the children back to Iowa City. His father, who couldn’t find work in the U.S., stayed in Abu Dhabi, and his parents eventually divorced.

“You can imagine growing up in war, and living in Saudi Arabia, where everyone is very religious, then coming to the U.S. to attend high school, where everyone is concerned about dating,” says Alshaibi. As his religiosity faded he grew increasingly interested in art. After studying painting for a year at the University of Iowa, he dropped out, but he continued to paint.

Because he was in the U.S. on his mother’s student visa, he couldn’t work legally. “It’s a very unstable, uncomfortable feeling, knowing your status is murky and you don’t want to be found out,” he says. “My mode was just survival.” He moved around a lot, working as a dishwasher and at other odd jobs in Boulder, Santa Fe, Providence, and Madison, occasionally taking college classes and showing his art in cafes. When he turned 21 in 1990, his mother’s visa no longer covered him and the INS told him he had to leave. But that August Iraq invaded Kuwait. “The Iraqi government was contacting my father [who was teaching in Jordan, a nominal ally of Iraq] saying they needed more soldiers to fight against the U.S. and its allies,” says Alshaibi.

He was sure if he went back he’d die in the war. He applied for political asylum, and nine months later he received it.

In the meantime, he started to feel the curiosity directed toward himself and other Arabs turning darker and more hateful. “I met a few soldiers in Iowa and I started hearing the word ‘sand nigger,'” he says. “At parties people would make racist comments disguised as jokes. ‘You’re the camel jockey.’ I kind of tolerated it.”

In Madison Alshaibi got turned on to the Cinema of Transgression, a New York underground film movement, and especially to the films of Richard Kern. “The people in his films looked like my friends,” Alshaibi says. “The music they had was the music I was listening to. I’d never seen something like that. It started opening my mind to what was possible.”

In 1994, Alshaibi moved to Chicago to enroll at Columbia College as a film student. He paid his way with loans and by working in the school’s equipment cage and at Nationwide Video. “Columbia trained us to think about the Hollywood model,” Alshaibi says. “We had to work on these larger-scale student projects and they followed that hierarchy.” Other students were making the movies; he was their production assistant, the gofer making coffee runs. “I thought, what’s the difference between this and washing dishes?”

Gravitating toward work that was more DIY, he found a community of likeminded filmmakers in Chicago and around the country who were screening their films in a proliferating underground festival and microcinema scene. “We shared that common desire to experiment with performance and makeup and costumes and do things that were more strange and not conventional,” he says. “It felt closer to painting or drawing—not this highly constructed method but a gesture I can do from the soul.”

Alshaibi got his green card in 1995, graduated from Columbia two years later, and went to work as a video and audio archivist for the Chicago Historical Society. One of his jobs was to digitize its collection of Studs Terkel interviews, and he and Terkel became close. “He taught me to listen to people,” Alshaibi says. “He put a little bravery in me and helped me recognize that what I had to say was relevant, how I can use my personal story to talk about things that affect other people.” An interview with Alshaibi appears in Terkel’s 2003 book Hope Dies Last.

In 2000 Alshaibi cofounded the Z Film Festival at Heaven Gallery, where it would run for five years. One of the first filmmakers it showcased was Kristie Drew, an MFA grad of the Art Institute. Alshaibi and Drew collaborated on a series of sexually explicit and sometimes violent shorts. “It was usually my camera aimed at her,” Alshaibi says. “These films we did together were our own secret little love letters, which is strange because if you see some of them they might come off as disturbing. But we enjoy them.”

They also maintained websites that were about as raw and transgressive—and highly political. They got noticed. After 9/11, Alshaibi received an anonymous e-mail that said, “The only good Arab is a dead Arab. Die sand nigger.”

“I was afraid to leave my house,” he says. “I was afraid to tell people my name. My mom suggested I change my name to cause less problems. But I stuck to my guns. I’m very proud of who I am and what my name is.”

Alshaibi has an aunt who in 2002 was chased by another motorist while she was driving in New Jersey. “He was trying to bump her and screaming at her and yelling profanity at her and calling her a terrorist,” Alshaibi says. Some time after that, she stopped wearing her headscarf. “When she had it on it was difficult,” he says. “Women who wear hijab are often attacked because they’re the most obviously Muslim-looking people.”

Alshaibi and Drew married in 2002, and Alshaibi became a naturalized American citizen soon after. “I was very proud to become an American citizen, and very troubled by what was happening to this country that I suddenly had to embrace as my home,” he says. In 2002 Kristie responded to the racial profiling of Arabs as terror suspects by predicting on her blog that the next bomber would most likely be a blond, blue-eyed woman—which she also happens to be. The couple was visited by a pair of FBI agents (and the visit was the subject of a Reader story). “They asked if she was planning on carrying out an attack on the United States or Israel,” Alshaibi says. “She said no. They told me I spoke really good English.” Alshaibi’s 2003 feature-length movie, Muhammad and Jane, tells the story of a romance between an American woman and an Iraqi man whose fears of the American government turn into a very real nightmare.

The U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, and Alshaibi told Terkel he wanted to make a film about returning to his homeland and visiting family there for the first time in 25 years. “He said, ‘You have to go,'” Alshaibi says. “He wrote the first check. Having Studs behind me, within a few weeks I raised the money.”

That movie turned out to be Nice Bombs. “I had this romantic idea that they got rid of the government and captured Saddam, and now Iraqis are free people and they’re going to have this open society,” he says. “I can move there and build a house and raise my family.”

A few weeks on the ground shattered his optimism. “It was like a record scratch. I felt very American. Iraqis kind of got used to living in war. It was difficult for me to go through the bombing and the threat of being killed or kidnapped or beheaded.”

In 2006 Alshaibi left the Historical Society for a job as a host and producer for Chicago Public Radio’s Vocalo.org. He was laid off in 2008 and spent a year unemployed, but in 2009 he was invited to apply for Kartemquin Films’s first diversity fellowship, underwritten by the MacArthur and Ford foundations. He proposed making “American Arab.”

The fellowship pays him a salary for a year, covers his production costs, and provides the normally self-reliant filmmaker with Kartemquin’s administrative infrastructure.

“I’m looking for stories of people who have an inner struggle with who they are,” Alshaibi says. “Unfortunately, being an Arab, that’s a common experience. Often we’re faced with something from the outside that makes us ask questions about who we are inside. People don’t go out seeking that kind of conflict, but when somebody comes up to you and says you’re a terrorist, you need to figure out how to respond to this.”

Alshaibi’s subjects include Marwan Kamel of the local band Al-Thawra (“The Revolution”), which figures in the nascent taqwacore, or Islamic punk, scene; Subhi Jasser, who moved to Chicago with his family in 2009 after he’d been kidnapped by militants in Baghdad and his house raided by U.S. soldiers; Ray Hanania, a Christian Palestinian-American columnist, radio host, and comedian who’s also a Vietnam vet and Cicero’s town spokesman; and Amal Abusumayah, an American-born Muslim woman whose headscarf was yanked in a Tinley Park grocery four days after last November’s Fort Hood shootings. (The case was prosecuted as a hate crime.)

“American Arab” is a little less than half done. Alshaibi plans to finish it next year, take it to festivals, and try to get it shown on television.

The Alshaibis recently rented a house in Fairfield, Iowa, where Kristie is studying transcendental meditation at the Maharishi Peace Palace. “I miss the country,” he says. “I miss having a big yard and seeing the night sky.” But on leaving Chicago, he realized for the first time that the city’s “truly my home. I found a place for myself here.”